This essay is mostly a commentary on The Myth of Analysis by James Hillman, a collection of three essays that were originally given as talks during the intellectual renaissance of the Eranos lectures in Ascona, Switzerland. Hillman has revised these talks into fluid prose with extended and layered argumentation. My commentary here functions more broadly as a response to Hillman’s paradigm of “archetypal psychology” and so draws upon his other works, including Archetypal Psychology (2013) and The Soul’s Code (1996).

Hillman represents an important intersection in intellectual, psychological, medical, and artistic contexts. His thesis is universal, his ethic is human. This essay cannot do justice to the nuance, density, and scope of Hillman’s contributions—it functions more as an aesthetic response.

Truth reveals itself in beauty.

—Rabindranath Tagore

The Myth of Analysis is a collection of three essays by James Hillman, delivered as talks in the 1960s and first published by Northwestern University in 1972. In these essays, Hillman deconstructs the paradigms of nineteenth-century psychoanalysis while elevating their import to an archetypal level. Hillman’s writing is part polemic—it critiques Freud’s sexual reductionism and builds upon Jung’s mythological emphasis. Calling for a “renewal of psychology”, Hillman manages to transcend and include his predecessors, while presenting his unique clarifications and emphases as “archetypal psychology”. A principle focus of Hillman’s polemic is the restoration of soul in psychology, of eros in psyche. His psychology of the soul presents an ontology of the soul with an archetypal epistemology that stands on the shoulders of analytical tradition.

The title has a double-meaning—the myth of analysis and the myth of analysis. It is a criticism of the limits of analysis and a calling to restore analysis to its mythical depths. Hillman primarily argues for a psychological paradigm beyond analysis in the consulting room. His “re-visioned” psychology fully embraces the imaginal realm of myth and archetype, of an ensouled life. Hillman’s urgency is a call to life from analysis, for a discovery of a relational destiny that is imagined, spirited, and embodied. His intention is to “penetrate analysis through to its mythical foundations”, transforming transference into the erotic, the unconscious into the imaginal, and neurosis into Dionysus.1 On this basis, Hillman argues for a new psychology that includes its namesake—psyche with logos: “Psychology thus becomes archetypal psychology in order to adequate to its subject, the psyche”.2

I. Sexual Traumata and the Wound of Love: From Sickness to Soul

Hillman criticizes and legitimizes Freud in a single breath. He regards the Freudian concept of the absent father as “comprehensively disastrous” while stating that “in choosing the Oedipus myth, Freud told us less which myth was the psyche’s essence than that the essence of psyche is myth”.3 Hillman’s assertion here is the essence of his overall message: the myths we use to describe the psyche are not merely pathic, they are mythic. Hillman rejects Freud’s psychopathology for a mythic psychology, asserting that we are not truly sick, we are only made sick by pathic ideas.

Throughout the text, Hillman’s subtle and nuanced perspectives place him outside of clear boundaries. At times, he criticizes Freud and Jung, casting the entirety of nineteenth-century thought into historical crisis. At other times, he accepts the inheritance of psychoanalytical tradition, a foundation he consciously builds upon. Hillman cannot accept Freud’s conclusions in Civilisation and its Discontents, where culture and humanity are lamented as nothing more than compensatory neuroses.4 For Hillman, “the world and its humanity is the vale of soul-making”.5 Echoing Keats, Hillman seeks to establish a renewed opus for psychology—the psyche itself—whose sole purpose is the making of soul.

Hillman consistently releases psychology from the analytic chambers of diagnosis and treatment to eros and imagination. The psyche is not in need of treatment, it is in need of expression. The psyche is not neurotic, it is creative. The psyche is not pathologically determined, it has a unique destiny. As Hillman says, “Has not each of us a genius; has not each genius a human soul?”6

The Myth of Analysis is divided into three parts, each part a single essay. The first part explores a self-referential hermeneutic where Hillman uses psychology to understand psychology. He transforms the Freudian eros of emotional-sexual psychopathology into a creative eros of anima and psyche. Hillman also expands the Jungian anima, describing it as an “archetype” that “transcends both men and women”. Hillman’s point is to articulate the anima as a structure of consciousness, as the psyche itself, no longer restricted in its application to men. Hillman writes:

The conclusions to which we are forced by the empirical data in analytical work are that anima becomes psyche and that it is eros which engenders psyche. Thus we come to one more notion of the creative, this time as perceived through the archetype of the anima. The creative is an achievement of love. It is marked by imagination and beauty, and by connection to tradition as a living force and to nature as a living body.7

We could easily mistake Hillman’s voice for that of a Romantic poet—Keats, Yeats, Emerson, Tagore. This is why Hillman footnotes the paragraph with a reference to Romantics, stating how they “provide a good example of the creative perceived through the anima, which led them to describe the creative as eros”.8 Hillman holds the Romantic period as a time in which there was an “extraordinary development of psychological insight”, noting Keats in particular.9 In doing so, he places his psychology of the soul within Romanticism as a philosophy of love.

Hillman moves the psychological consideration from the pathological to the mythological with grace and insight, asserting that “the search for illness makes for illness”.10 For Hillman, it is the psychology of illness that makes us sick. An archetypal psychology would not see pathology, but mythology, not sickness, but soul.11 His issue with Freud’s Oedipal pathologies seems to stem from their condemnation of the soul to illness, where the soul “has no apparent redemption”.12 He resolves this by “transposing the emphasis from oral and genital to the creative”—wherein “we return to the childish, less for fulfilling or transforming oral gratifications and polymorphous perversity than for the sake of regaining the childlike”.13 Here, Hillman makes clear his departure with Freud, no longer viewing childhood as the context of pathology but instead as the platform of purpose. It would be an oversimplification to say that Hillman eschews childhood pathology—it is more that he regards childhood wounds as “wounds of love”, not as “nutritive and sexual traumata”.14

“Trauma” comes from seventeenth-century Greek and literally means “wound”. A wound is not merely a site of “damage”, a wound is an opening that does not require a bandage—“it is mainly through the wounds in human life that the gods enter”.15 The root-trauma of the soul is the wound of love. The “wound of love” is a phrase featured in Adi Da’s discussions of human development and growth, where it is employed as the antidote to the Oedipally-born rituals of betrayal and rejection. Adi Da writes:

When you love one another thus, there is nothing cool about it. What I mean by such love for one another is that you become wounded by love, surrender yourself to live in that domain and make your relationships about love. Be vulnerable enough to love and be loved. If you will do this, you will be wounded by love. You will be wounded, but you will not be diseased.16

Thus, the wound of love is not conceived as etiology or pathology, but as the necessity of the human heart to love. We can move from sickness to soul, from trauma to wound. The trauma of birth and the subsequent traumata of childhood need not be seen merely as hurts, but as incisions in the soul made by life itself to open its spiritual pores and fill the feeling chambers again with the heart of life.

Hillman does not seek to criticize the validity of Freud’s theories as much as he wishes to show a limitation in interpretation—he otherwise expresses indebtedness to Freud as the genesis of the mythic in the psychic. Hillman writes, “The Freudian error lies not so much in the importance given to sexuality; more grave is the delusion that sexuality is actual sexuality only, that phallus is only penis”.17 This is the age-old criticism of Freud’s materialism and its reductionistic interpretations. Hillman’s expansion of “penis” to “phallus” represents a movement away from the thing itself and toward its archetypal image. Eros is no longer the Freudian instinct, it is the creative work of love, the opus of the soul. We have moved from penis-envy to eros-envy.

To support his argument that Eros is more than sexuality, Hillman uses the example of so-called “Platonic” love:

We know from practice that love and sexuality are not identical. There is an eros, wrongly called Platonic, that omits the sexual, just as there is a sexuality without eros.18

Hillman presents a nuanced counter to Freud without invalidating Freud’s contributions to psychoanalysis. For example, Hillman recasts the Freudian instincts, articulating Eros and Thanatos as a singularity:

Eros leads the soul, not only as the Freudian life-instinct separated from and contrary to Thanatos; Eros is also a face of Thanatos, has death within it (the inhibiting component that holds back life), and leads life into the invisible psychic realm “below” and “beyond” mere life, endowing it with the meanings of the soul given by death.19

This re-visioned psychological eros is liberated from pathogenesis, untangled from etiology, freed from “case material”. Hillman’s psychology transcends the individual as a problem and in doing so leaves behind the liability of the clinical. On this point, Adi Da comments that “the disadvantage of clinical therapy of any kind is that it presumes a problem, and even meditates on it.”20 Hillman addresses these concerns by recasting problem into purpose, pathology into destiny, case into character, suffering into eros, psyche into soul.

II. Emanation and Animation: Pluralistic Animism and Polytheistic Psychology

In Part Two of The Myth of Analysis, Hillman deconstructs the nomenclature of psychological practice, which he regards as a “tool of the establishment”.21 He accuses psychological language of insulting the soul, as “it would sterilize metaphors into abstractions”.22 He returns to the Romantics, this time citing Coleridge as an example of how depth psychology “once spoke with a living tongue”.23 His clearest critique of psychological language places it within the confines of the “nineteenth-century mind”:

Our psychological language is largely post-Napoleonic. Its development parallels the industrial revolution, positivism, nationalism, secularism, and all that is characterized as the “nineteenth-century mind”. Our language represents specifically the academic and medical mind of the nineteenth century. Psychology and psychopathology are children of the late Enlightenment, the hopeful Age of Reason as it hardened into an Age of Matter.24

Hillman is critical of the mood and language of scientific materialism, which he argues has thoroughly usurped psychology. Even Freud and Jung are seen as outliers in this context, unable to be fully accepted academically or clinically by modern psychology. Hillman writes that “the soul lost its conviction in itself as a timeless intangible in vivid touch with timeless intangibles”.25 His view is consistent with indigenous worldviews, especially pluralistic animism.

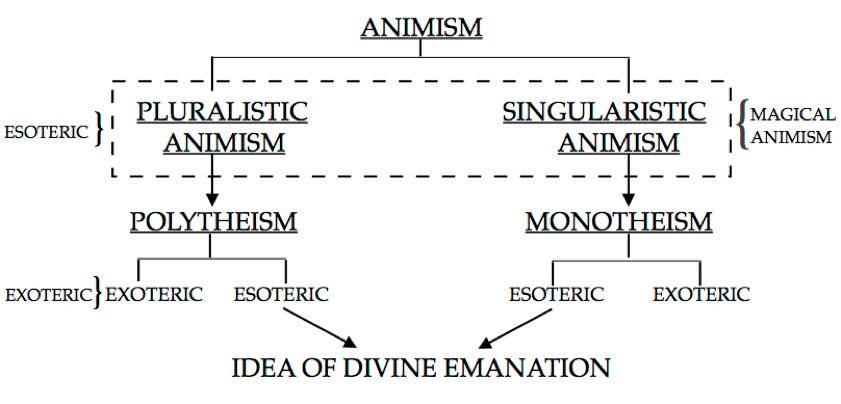

In an introduction to Adi Da’s text, Nirvanasara, Georg Feuerstein defined pluralistic animism as “the experiential projection of multiple, discrete ‘energies’ or invisible agencies onto nature. With increased hypostatization this led to the postulation of a plurality of deities (personalized, multifunctional agents), often organized into a pantheon”.26 Pluralistic animism is the antecedent of polytheism, and polytheism can be further subdivided into esoteric and exoteric aspects. Feuerstein illustrates this in the following diagram:

Adi Da places animism within the general umbrella of “emanationism”, a worldview that can be contrasted with “materialism”. The emanationist view sees the world as a divine emanation, animated either singularly or plurally. The materialist view, on the other hand, sees the world as an observable set of causes and effects. Feuerstein summarizes:

This is the notion, based on the “energic” world-view of animism, that “conceives of all of Nature (including every part, thing, or individual being) to be set upon, pervaded by, or at best emanated from an ultimate (and thus Divine and Transcendental) and invisible (and thus spiritual) Source.” Thus, according to this theorem, the visible world is in some sense dependent on the Invisible. The universe may be understood either in terms of its being a de facto emanation of the Divine or as being coessential with or, thirdly, eclipsed by the ultimate Reality. In contrast to the emanationist view of reality, materialistic schools of thought—from scientific materialism to Hīnayāna Buddhism—rest on an explicit or implicit denial of the ideal of emanation.27

We can see that Hillman’s critique is in relation to a “Nirvana principle”, a counter to a materialistic worldview that eliminates soul in the mechanics of causation and the mortality of impermanence. We can thus position Hillman’s arguments within the “emanationist” worldview, coupled with its calling for a polytheistic psychology, re-infused with pluralistic animism—a psyche re-populated by its gods.

The Buddhist doctrine of anattā and śūnyatā both reject the notion of a soul, which they interpret as the implication of an individually-existing entity or substance that endures physical death. Nāgārjuna’s doctrine of emptiness most radically asserts the non-existence of an independent soul. Hillman, however, asserts that psyche is soul is self, in a re-formulation of the Upanishadic doctrine of ātman. Paradoxically, the Vedāntic notion of ātman is not truly an individual soul (or ego-principle), but is rather conceived as the non-separate life-giving spark of a monotheistic, self-unified, and non-dual God-principle (Brahman). Such is the ultimate monism of Vedānta, a view that springs from the stream of “singular animism” compared to Hillman’s pluralism and polytheism. Perhaps the closest Hillman comes to a Brahmanic principle is in his discussion of the Neoplatonic and Hermetic world-soul (anima mundi or paramātman), asserting a worldview of living relatedness between microcosm and macrocosm. Hillman confirms the resonance of his views with Eastern doctrine when he writes:

As soul (in the anima definition of Jung) is the archetype of life, self is the archetype of meaning. Its analogies tend to be drawn from philosophy (self-actualizing entelechy, principle of individuation, the monad, the totality) or from the images of mystical theology and the East (Atman, Brahman, Tao).28

Hillman’s polytheism most closely resembles the spirited world of the East, in which the human being not only lives within the world but systematically corresponds to it. In Asian cultures, this resonance is described in mythological terms, where the natural world becomes imbued with unseen animating principles described as “spirits”. These spirits are given elemental associations and a guardian function. As the animating forces of the world, they become vital principles, essential to the laws of natural order. Perhaps these ancient worldviews exemplify an ancient psychological paradigm, as they not only conceived of a polytheistic world, but a polytheistic psyche, visible in dreams.

The pluralistic animism of Tibet is applied in medical theory as an ecological paradigm of illness. Where nature is debased, spirits are “provoked”, transforming from protectors to etiological factors. This is a subtle category of illness, but it has a diagnostic method and a therapeutic instrument. In Tibet, such spirit-pathologies were understood as needing a religious cure and would be taken to the lama instead of the menpa. Yet, Tibetan medical history shows a profound interweaving of religion and medicine, where doctors were equally priests and shamans. The Tibetan word for a physician, menpa, has two meanings: “one who benefits others” and “medicine person”—the latter meaning in particular transmits a shamanic connotation. Similarly, the Chinese word for a healer was originally wu (巫) meaning “shaman”. Later, the term yi was used as a reference to “physician”, and the two were hybridized as wuyi, a shaman-physician.

The English word physician comes from the Latin physica, meaning “things relating to nature”. A “physician” is therefore concerned with nature, is a person of nature, a restorer of natural order, a shaman and a surgeon. Hillman calls for a psychology of the soul that requires the “analyst” to become physician of the psyche. Analysis has reached its end-game, says Hillman, the psyche is deadened in its parsing. We need not analysis, but mythos; not science, but nature. The only therapy here is vis medicatrix naturae—the self-healing power of nature itself.29

The therapeutic axiom of psychoanalysis is to make the unconscious conscious, a principle Hillman conceives in a visionary sense of seeing an archetypal image, not analyzing it. His method recalls the Tibetan practice of “dream yoga” (rmi lam rnal 'byor) which details the process of lucid dreaming and its role in assisting the practitioner to transcend the “dream” of existence, especially in the after-death states (or bardo). The Tibetan description of the after-death experience is filled with deities—benevolent and wrathful—visions that can be interpreted psychologically as archetypal images. Adi Da said, “During life, you make mind, and after death, mind makes you”, agreeing with the Tibetan view of the after-death process as free of body but filled with psyche. The Tibetan practice of dream yoga consists of visualization and meditative exercises, usually performed while falling asleep. The goal of this practice is to engender a lucid state of awareness that the practitioner becomes increasingly able to consciously direct. However, the Tibetans also look to dreams for prophecy and revelation. Many Tibetan teachings, religious and medical, are considered dream revelations known as gter ma (literally “hidden treasure”). Thus, dream yoga is not only a practice of lucidity, but a method of revelation. Indeed, the process of becoming conscious in the dream symbolizes the goal of traditional psychoanalysis in “making the unconscious conscious” and of archetypal psychology in “sticking to the image”. We need lucidity in the psyche or our soul will never recognize its images and so will fail to be made.

Continuing his critique of psychoanalysis, Hillman argues against the concept of “the unconscious”, because it implies a lack of consciousness: “the term ‘unconscious’ is suitable for describing states where consciousness is not present”.30 The unconscious is not dormant or asleep, nor is it “un” in any sense, Hillman asserts. In agreement, Adi Da clarifies the meaning of unconscious as “pre-mental” rather than “asleep”:

If you “consider” yourself in terms of your history, your characteristic patterns of reaction, your characteristic way of relating to people, your characteristic sexual life and so on, you will eventually begin to see what is otherwise invisible and not mentalized—what is pre-mental. That is why we call it unconscious. It is not unconscious in the sense that it is asleep. It is unconscious in the sense that it does not exist in the form of the thinking mind. It is awake all the time. Even when you go to sleep and dream at night, it is still making images for you. It does not go to sleep any more than the fundamental Consciousness goes to sleep.31

The unconscious is “invisible” and “pre-mental”. It is termed “unconscious” because it represents a layer of the psyche that we are not ordinarily conscious of. Thus, “unconscious” says more about the human condition than the nature of the psyche itself. As Adi Da notes, the unconscious is “making images”, and images are its only means of communication (as Jung so clearly articulated). Hillman expands on these insights and rightly terms the unconscious “the imaginal”, restoring its original pattern of myth and magic. Thus, the unconscious is no longer a source of pathology, but a source of mythology; not a mind of analysis, but a vision to be seen; not a thing to be cured, but a soul to be made.

This leads us to Hillman’s overarching point: archetypes recover the myths of the psyche, and this recovering of the mythic is the true therapeutic of the soul. The images of the unconscious are not symptoms but creative visions. Hillman’s views largely agree with Jung, but he argues for a methodology beyond the “myth of analysis”, beyond the regressive inquiry into memory and dream, beyond the pathologies of childhood, and into the living myth constellating the psyche in the present, shaping through eros a destiny of love.

III. Archetypal Praxis: From Clinic and Case to Archetype and Image

Psychoanalysis began in dreams and, for Hillman, has its therapeutic in the mundus imaginalis. Archetypal psychology recasts life in the context of dream, living a poesis of fantasy, personality as the image of myth. His praxis is a non-praxis that re-visions the clinical as the imaginal, life as story, being as art, therapy as the “poetic basis of mind”. Elaborating on the practice of archetypal psychology, Hillman writes:

An essential work of therapy is to become conscious of the fictions in which the patient is cast and to re-write or ghost-write, collaboratively, the story by re-telling it in a more profound and authentic style. In this re-told version in which imaginative art becomes the model, the personal failures and sufferings of the patient are essential to the story as they are to art.32

The transition from analysis to an “image-focused therapy” is Hillman’s most fundamental vision. In doing so, he casts city and soul into dream, extending its authentic fantasy beyond the boundaries of the treatment room, a therapy “beyond the encounter of two persons in private . . . re-imagining the world within which the patient lives”.33 Hillman moves the theory of therapy from a vertical encounter in history to a horizontal vision in immanence. Therapy should assist the realization of a poetic basis in mind “in actuality, as an imaginative, aesthetic response”.34 Hillman unchains therapy from analysis and places it in the full scope of the imaginal world, which he argues extends “both the notion of the ‘psychological’ to the aesthetic and the notion of therapy from occasional hours in the consulting room to a continual imaginative activity”.35

Thus, archetypal psychology has no didactic, no goal, and no constant form. Its only task is “to return personal feelings . . . to the specific images that hold them”.36 And, in “sticking to the image”, to bestow perspective and purpose. Hillman likens the practice of archetypal psychology to the Jungian technique of active imagination. Active imagination returns the focus of therapy to the image itself—its aesthetic signature and the psychological response it evokes. Active imagination is another way to describe dreaming, calling us to consider therapy as an activity of fantasy unfolding in the context of dream-images. Hillman makes this consideration explicit when he states that “the dream as an image or bundle of images is paradigmatic, as if we were placing the entire psychotherapeutic procedure within the context of a dream”.37 In a movement away from the dream-focused analysis of Freud and Jung, Hillman re-constitutes the purpose of dream, not as the focus of therapy, “but that all events are regarded from a dream viewpoint, as if they were images, metaphorical expressions”.38 Hillman radically enlarges the ontology of dreams when he places the patient within dream, rather than the dream within patient: “The dream is not in the patient and something he or she does or makes; the patient is in the dream and is doing or being made by its fiction”.39

We see the emphasis of Hillman’s praxis in traditional cultures who not only valued dreams, but lived on the basis of them. This emphasis is echoed by Adi Da in his description of ancient culture as dream-culture:

In the ancient setting, people were involved in the illusory mind of the dream-state. They were not involved in anything extraordinary relative to verbal sophistication and conceptual mind. They lived in a very straightforward sensory context, from day to day, in the waking state—but the dream-mind was the form of mind in which they were principally (or most deeply) involved, and to which they reached for help, and consolation, and wisdom.

If you examine the most ancient (and, even now, traditional) literature, you will see that it is the literature of people who took the dream-mind to be the senior reality—the reality that (in their understanding) indicated their real, true, and ultimate destiny. And that dream-mind, or dream-“world”, was populated with the “deities”, archetypes, symbols, and whole systems of myth that became the resource of ancient (and, even now, traditional) “religion”.40

Hillman’s image-focused therapeutic calls for a restoration of the dream-mind and the dream-world. His re-visioned psychology is polytheistic, populated by its gods. The dream-world is thus religious, a source of the sacred. Hillman consciously places archetypal psychology within this dream-world of the mundus imaginalis, moving beyond an ego-based psychology of secular humanism to a soul-based psychology of the anima mundi. In doing so, Hillman characterizes archetypal psychology as a ritual with a religious basis, rather than a job with a secular goal. He notes that a “polytheistic psychology is necessary for the community of culture”, coupling monotheism with the hero-myth of “secular humanism”. Seen in this way, psychotherapy becomes a sacred act with an inherently religious instinct:

[Archetypal psychology] shifts the ground of the entire question to a polytheistic position. In this single stroke, it carries out Freud’s and Jung’s critiques to their ultimate consequent—the death of God as a monotheistic fantasy, while at the same time restoring the fullness of the gods in all things and, let it be said, reverting psychology itself to the recognition that it too is a religious activity. If a religious instinct is inherent to the psyche as Jung maintained, then any psychology attempting to do justice to the psyche must recognize its religious nature.41

While casting psychology as a religious activity, Hillman is careful to distinguish it from faith and worship, making clear that gods are not worshipped, they are imagined as “cosmic perspectives in which the soul participates”.42 For Hillman, gods are synonymous with the populous of myths, and therefore places rather than entities. Gods and myths “make place for psychic events that in an only human world become pathological”.43 Indeed, the pathology of the modern world is not merely the trauma of childhood, but the narrowed context of life, made only human in a world that is intrinsically more than human.44 This is where Hillman’s psychology becomes an eco-psychology, resurrecting the ancient setting of the dream-world, with its dream-mind and dream-images. Archetypal psychology thus shares its motive and vision with traditional medicine and astrology—to restore the human being to the context of relatedness, placing the human in a more-than-human world, where “microcosmic things” are seen in “rapport with macrosomic gods”. The value of archetypal psychology is in its ability to re-place the isolated human in the populous of polytheism, related again in diversity, mirrored within itself—the human being as a reflection of the kosmos.

The goal of archetypal psychology is not to interpret the imaginal world back into the person—it is to place the human into the mundus imaginalis. It does not seek explanation or “reversion through likeness of an event to its mythical pattern”.45 Rather, its aim is an awakening to archetypal, imaginal, and mythical life, restoring “an archetypal sensitivity that all things belong to myth”.46

IV. The Romantic Fallacy: Pre, Trans, and Paradox

As with any great thinker, Hillman has his critics. A fundamental critique is made by philosopher, Ken Wilber, who criticizes Hillman for committing the “pre / trans fallacy”:

Many psychological theorists who are investigating the subtle line of development—e.g., the Jungians, Jean Bolen, James Hillman —often confuse the lower, prepersonal levels in the subtle line with the higher, transpersonal levels in that line, with unfortunate results. James Hillman, for example, has carefully explored the preformal, imaginal levels of the subtle line, but constantly confuses them with the postformal levels of the subtle line. Just because theorists are working with dreams/images/visions does not mean they are necessarily working with the higher levels of that line . . . .47

Wilber’s developmental theory is composed of waves, streams, states, and lines that attempts to account for an apparently incongruent developmental process (e.g. one can be highly developed in the cognitive line but undeveloped in the spiritual line, etc.). But each line is a hierarchy from “lower” to “higher”. Wilber asserts that Hillman’s psychology is concerned with “preformal, imaginal levels of the subtle line” and that these are confused for “postformal levels”. His critique borrows Piagetian terminology, but how do we know that the images of the psyche are of a lesser nature than “postformal” levels of the “subtle line”? The ontology is confused—all things of a subtle nature are imaginal, only the causal dimension is formless. And his distinctions between “preformal” and “postformal” is theory, and theory alone.

Wilber conceives of animism, shamanism, and magical-mythical consciousness as idealizations of a pre-personal condition that is not actually trans-personally attained. Wilber illustrates his theory by placing Freud in the “pre” category (Freud reduces transpersonal states to pre-conscious conditions e.g. the unconscious is the seat of instincts) and Jung in the “trans” category (Jung elevates pre-conscious states to transpersonal significance e.g. the unconscious is the source of higher truth). On Jung, he writes:

Jung is definitely most guilty of the pre/trans fallacy. He simply does not differentiate with sufficient clarity between prerational and transrational occasions, and thus he tends to elevate prerational infantalisms to spiritual glory, for no other reason than they are not rational.48

To anyone acquainted with the works of Jung, this reading is patently oversimplified.49 Why is Wilber so ready to demote the psyche to an infantalism that stands diametrically opposed to spirituality? Is not spirituality equally a mythos, languaged in mythology, archetypally expressed? Wilber is a philosopher, not a clinician—this is why he can afford such abstractions. The clinic reliably renders insights of an exceptional nature and its therapeutic gnosis defies every category that attempts to place it.50 Perhaps a more significant issue with Wilber’s “integral theory” than its criticisms of Jung and Hillman is its view of indigenous animism as an archaic stage in human development and history.

Wilber’s “pre / trans fallacy” describes the “magical and mythical” worldview of indigenous peoples as a fallacy that idealizes the natural world and falsely projects a transpersonal status onto it. For Wilber, nature is not transpersonal, but prepersonal; not animated but unconscious. His argument is that pre-rational and trans-rational states are both non-rational, and thus are easily conflated. His goal is to distinguish authentic transpersonal states of consciousness from pre-personal states of consciousness—prepersonal states are unconscious and undifferentiated, transpersonal states are conscious unions. Where Hillman calls for a return to the childlike, Wilber cries fallacy! for the imaginal world of the child is not a transpersonal glimpse but an immature fantasy.51

Hillman, however, does not give myth or archetype a transpersonal ontology, as Wilber suggests. In Archetypal Psychology, Hillman presents archetype as the image itself, not as a pointer beyond itself—“the image has no referent beyond itself”52 and “images don’t stand for anything”.53 The image is thus irreducibly present, as itself—not an object or thing, not “what one sees, but the way in which one sees”,54 its locus being “the awakened heart”.55 Hillman sees archetype as neither pre-personal nor transpersonal, but non-personal:

An archetype is psychologically “universal,” because its effect amplifies and depersonalizes . . . Thus, the universality of an archetypal image means also that the response to the image implies more than personal consequences, raising the soul itself beyond its egocentric confines (soul-making) . . . .56

Despite his emphasis on soul, Hillman does not characterize archetypal psychology as a transpersonal psychology, but rather a psychology of “mythical realism”.57 Hillman maintains an ambiguous and multivalent usage of “soul”—it is “used freely without defining specific usages and senses in order to keep present its full connotative power”.58 Thus, “soul” is less a metaphysic and more a metaphor, less a thing and more a value. The human being and the world are both ensouled by the same psyche, but “the human being is set within the field of soul; soul is the metaphor that includes the human”. It is in his consideration of the relationship between soul and myth that Hillman makes clear the non-personal rather than transpersonal nature of archetypal image:

Even if the recollection of mythology is perhaps the single most characteristic move shared by all “archetypalists,” the myths themselves are understood as metaphors—never as transcendental metaphysics whose categories are divine figures.59

In Wilber’s nested developmental hierarchy, what is pre cannot be trans, but what is trans necessarily includes what is pre. The fallacy thus arises when pre is seen as being trans, when lack of development is mistaken for transcendence. Wilber’s view is that while children share certain features with transpersonal states of consciousness, they are, in fact, in a pre-conscious condition: the participation mystique of a child is not the evidence of an Enlightenment lost in adulthood, rather the child has an undeveloped ego. Hillman might accuse Wilber of reading the adult into the child, and thus viewing the nature of childhood development backwards. Hillman makes this criticism of Freud, arguing that his theories of childhood psychopathology are based largely on adult patients, that Freud has not really seen or heard the child, but only reasoned the childlike through the adult.

However, Wilber’s pre / trans fallacy does usefully delineate a confusion that can miss the mark of true spirituality and the structures it unfolds through. The pre / trans fallacy rightfully rejects a regressive notion of spiritual growth as a “path of great return”60 to an earlier (idealized) state of being. Wilber asserts development as a growth in consciousness, not a return to unconsciousness. Wilber also frames the process of growth as an ever-widening consciousness, where contradictions are naturally resolved at each ring of growth by “transcending and including” what precedes it. Thus, everything is partially true, but the highest stage will necessarily have the most “integral” view of everything that precedes it (which it now comfortably contains).

Despite these theoretical strengths, the pre / trans fallacy fails us clinically in its inability to fully encompass a paradoxical view of development that is not stacked upon itself in stages, but that encircles itself in historical contradictions. Of this, Hillman writes:

Perhaps we are obliged to abandon the notion of development, since it has become a linear idea, requiring continuity. Besides, our own lives tell us that the ego does not move like a hero on his course; this sort of ego is a superego in whose shadow loom the complexes of inevitable psychopathology . . . The movement of the imaginal ego should be conceived less as a development than as a circular pattern.61

Hillman moves past a linear developmental therapeutic, embracing the image of a spiral dynamic. Wilber moderates his ladder by asserting that regression to an earlier stage of development is possible at any stage. However, he considers this regressive spiral a developmental pathology, where Hillman sees a natural “movement of the imaginal”. We can place Hillman’s view in agreement with Jung:

There is no linear evolution; there is only circumambulation of the self. Uniform development exists, at most, only at the beginning; later everything points towards the centre.62

Developmental ideas embrace the historical and temporal nature of growth, while circular ideas see the myth of progress. It is not possible to look at human culture today and think that we have truly “evolved” over time. On the contrary, the worldviews of indigenous cultures is what will foster an ecological consciousness that exists in relatedness with the livingness in all things. In my criticism of the developmental hierarchy that Wilber’s theory (and fallacy) rests upon, I have quoted two figures who Wilber considers guilty of committing the Romantic fallacy. I have used Romanticism to defend Romanticism, much as Hillman has used psychology to re-vision psychology. But is this not also the myth of analysis? Perhaps analysis is its own fallacy, made rich by abstractions. Wilber commits the myth of analysis, casting his fallacies like stones to the past to project a present abstraction for a future that remains only knowable, not imagined. Wilber’s theories, while logical and sensible in one regard, remain neat conceptual boxes that miss the mark of the more paradoxical dynamics of a life perceived. Too much theory turns metaphor into abstraction, soul into matter, psyche into mind. In truth, nature is a möbius strip of intersecting curves and shapes—only man reads himself into nature, drawing straight lines that square the circle, surrounding and destroying the center of life, while proclaiming: progress!63

V. Superior Man, Inferior Woman

This brings us to the final part of Hillman’s opus: psychological femininity. Hillman peers into the unconscious of psychoanalysis, uncovering the misogyny of the nineteenth-century mind that informed it. He posits that the imaginal world64 has been lost in the paradigm of feminine inferiority / masculine superiority. He equates the imaginal with the feminine, calling for a psychology beyond the consulting room of European men that truly includes the feminine.

The paradigm of archetypal psychology re-captures this lost world of love and its intrinsic bi-sexuality, where all polarities exist at once in coniunctio. There is no superiority or inferiority or even development. Rather, it is through love that we re-capture our imaginations, that we come to know observation itself as a form of fantasy, and embrace the imaginal as the only true therapeutic for the psyche.

In contrast, Wilber’s philosophical outlook continues the trend of the “nineteenth century mind”, remaining a male hermeneutic, masked in misogyny, promotional of patriarchy. This is made plain in Wilber’s dismissals of historical misogyny65 and even moreso in David Deida’s book, The Way of the Superior Man, a title that accurately reflects the contents as an opus of patriarchy.66 The book was endorsed by Wilber as a guide for the “non-castrated male”, an evocation of Freud’s “castration anxiety” and a fitting reflection of its embeddedness in the pathological male.

Myth and magic are systematically lessened by men who place woman on the lower rung of the evolutionary ladder, only redeemable in height by the superior man, towering from above to tend the feeble of its calling. Animism embraces and elevates nature as prima materia, not merely as ground to built upon. Nature-as-woman is the ancient understanding of indigenous peoples, cultures the diseased man pisses upon while proclaiming his province, uncastrated in his own penis-envy.

For Wilber, indigenous worldviews do not represent an authentic esotericism, but a primitivism confused for insight. This disavowal of indigenous tradition by yet another white male reeks of privilege—the ignorance it insipidly perpetuates, the lies it destructively disseminates. Like a bad seed blown across the fertile fields of a natural landscape, everyman stands envious in hand of all the shots he can trigger, for and against his own mother. Analysis is thus self-castrating, eros absent of its father, bastardized in thought, incestuous in action.

What is the purpose of locking Romanticism in the chambers of fallacy? So that it too can be taken, raped of its imagination, flowered for profit? It is man who wishes to destroy the garden—as Hillman says, it was “first Adam, then Eve”. Adam is made in the image of God, but Eve is born of Adam. Eve is the casua formalis, the cost of humanity, and the price she must pay, perpetually, for it. She is the eros that psyche must not have, the soul she can never engender but only birth in man-made clinics, cold and quantified in her removable womb. Have we forgotten there is no birth without her?

Hillman is set to establish a psychology that owes its heritage to the indigenous traditions of animism and alchemy, of nature and soul. He picks up the lost threads and misplaced meters of the Romantics, freeing its heart-strings from the jails of fallacy, to make rhyme again in the garden of soul and of spirit.67

VI. Restoring the Pleasure Dome: Psyche with Eros

In Xanadu did Kubla Khan / A stately pleasure-dome decree.

The “pleasure dome” of Coleridge’s poem was renewed by Adi Da as a symbol for the sacred feminine principle of life:

Everything about woman . . . everything about the domain of feeling and senses, and pleasurable association with the feeling and sensuous domain (or sense domain) is corrupt at the present moment, and opposed . . . Woman is opposed— that which woman is, that which she incarnates, that which her pattern is about. The “She” altogether requires mankind to be integrated with it, as the core of life . . . This fundamental transformation is something that I am calling for—the restoration of the Pleasure Dome as the context of human life.68

In his poem, Coleridge calls for the preservation of the “pleasure dome”, the palace of the creative instinct, the beautiful spaces of eros. The pleasure dome is the palace of the imaginal world, of the more-than-human psyche and its natural life. For Adi Da, the pleasure dome is synonymous with the feminine, with the “sensuous domain” of nature, of nature as woman, and of woman as feeling. How can we heal if we cannot feel? How can we love if we cannot embrace? The pleasure dome is where the psyche feels and heals. The pleasure dome is the birthing palace, where the psyche is born again in eros—recovered in creativity, awakened to love.

Hillman makes explicit everything Freud discovered and Jung implied. He applies psychology to psychology and so engenders a new wholeness, psyche with logos, therapy in life, life in mundus imaginalis. Archetypal psychology takes its concern and places it outside of the clinic, in the room of the psyche itself, in its living land.

The Myth of Analysis is a significant work, written at a critical juncture of psychological inquiry. It lays bare its predecessors while embracing their tradition. It deconstructs analysis, pathology, and the context for therapy. Hillman dismantles his own profession and levels its playing field—with polemic, insight, and passion. His writing is a cry and call for an archetypal hermeneutic, for a return to an older understanding, a re-tracing that encircles the opus of psychology.

The uroboros continually returns us to the opus of Hillman’s archetypal psychology: the soul itself. The therapy needed by the soul is not in analysis, but in life. The incarnation of eros is the embodiment of love, through which the lines of destiny are lived. The Romantic reason is unreasonable—it professes love in a temporary world, worships nature in her ever-changing shapes, and maintains the ecological eros of an encompassing psyche.

“The wound of love is the ‘hole in the Universe’”.69 Eros enters psyche through the wound of love, warmed in the radiant chambers of the heart. If we cannot thus imagine the Beautiful, then the Beloved has no form for sight, no body for Truth, and no revelation of Reality. Only love can rediscover the hidden root of life in aesthetic ecstasy—breathing in Beauty, speaking in Truth, and living the Real in a world of dreams.

James Hillman, The Myth of Analysis (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1972), 8.

Ibid, 13.

Ibid, 16.

Hillman’s view is nuanced. In Alchemical Psychology, he says, “Our neurosis and our culture are inseparable” (p. 19). He does not see this recognition as an end-point, but as the starting point of a “rectification” of language: “I am also harkening back to Confucius who insisted that the therapy of culture begins with rectification of language”. (p.19).

Hillman is fond of this quote from Keats which summarizes the essence of his archetypal psychology: “Call the world, if you please, ‘the Vale of Soul Making’. Then you will find out the use of the world…”.

James Hillman, The Myth of Analysis (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1972), 39.

Ibid, 54.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid, 59.

In Re-Visioning Psychology, Hillman describes his psychological paradigm in four parts: “personifying or imagining things”, “pathologizing or falling apart”, “psychologizing or seeing through”, and “dehumanizing or soul-making”. The second part of the book offers his perspectives on “pathologizing”, building on the perspectives mentioned here.

James Hillman, The Myth of Analysis (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1972), 60.

Ibid, 61.

Ibid.

James Hillman, Archetypal Psychology Uniform Edition of the Writings of James Hillman, Volume 1 (Putnam, CT: Spring Publications, 2013), 46.

Adi Da Samraj, The Complete Yoga of Human Emotional-Sexual Life (Middletown, CA: Dawn Horse Press, 2007), 99.

James Hillman, The Myth of Analysis (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1972), 63.

Ibid, 65.

Ibid, 77. Hillman cites Norman O. Brown’s Life Against Death near this passage.

Adi Da Samraj, “The Treasure Consideration” (Middletown, CA: Dawn Horse Press, 1997), 26.

James Hillman, The Myth of Analysis (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1972), 122.

Ibid, 121.

Ibid.

Ibid, 125.

Ibid, 132.

Georg Feuerstein, Introduction to Nirvanasara by Bubba Free John [Adi Da] (Middletown, CA: Dawn Horse Press, 1982), 7-55.

Ibid, 32.

James Hillman, The Myth of Analysis (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1972), 207.

Hillman criticizes the biological viewpoint as the “naturalistic fallacy”. However, this is not a criticism of naturalistic worldviews as it is the “nature” of scientific materialism.

James Hillman, The Myth of Analysis (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1972), 174.

Adi Da Samraj, “The Treasure Consideration” (Middletown, CA: Dawn Horse Press, 1997).

James Hillman, Archetypal Psychology. Uniform Edition of the Writings of James Hillman, Volume 1 (Putnam, CT: Spring Publications, 2013), 51.

Ibid, 52.

Ibid.

Ibid, 53.

Ibid, 50.

Ibid, 51.

Ibid.

Ibid, 52.

Adi Da Samraj, The Aletheon (Middletown, CA: Dawn Horse Press, 2009), 1277-1278.

James Hillman, Archetypal Psychology. Uniform Edition of the Writings of James Hillman, Volume 1 (Putnam, CT: Spring Publications, 2013), 43.

Ibid, 42.

Ibid, 43.

The phrase “more than human” is used by David Abram in his book, The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human World (1997). Abram’s book was positively endorsed by Hillman and represents a foundational exploration of an indigenous worldview that became the basis of “eco-psychology”.

James Hillman, Archetypal Psychology. Uniform Edition of the Writings of James Hillman, Volume 1 (Putnam, CT: Spring Publications, 2013), 43.

Ibid, 44.

Hugh and Amalia Kaye Martin, The Fundamental Ken Wilber (2008).

Ken Wilber, The Eye of Spirit (Boulder, CO: Shambhala Publications, 2001), 239. For Wilber’s full critique of Jung and archetypes, see pp. 238-241.

This is not to say that Wilber is not well-read—he is extremely well-read in the works of Freud and Jung, but his conclusions remain oversimplified.

While I am critical of the clinical applicability of Wilber’s philosophies, some serious attempts have been made to integrate his theories in a clinical context. Notably, Lonny Jarrett has sought to apply Wilber’s integral theory in the context of Chinese medicine, an approach he details in Deepening Perspectives on Chinese Medicine (2020).

The value of the childlike is also expounded by Jesus in Matthew 18:2-5: He called a little child and had him stand among them. And he said: "I tell you the truth, unless you change and become like little children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven. Therefore, whoever humbles himself like this child is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven. And whoever welcomes a little child like this in my name welcomes me”.

James Hillman, Archetypal Psychology. Uniform Edition of the Writings of James Hillman, Volume 1 (Putnam, CT: Spring Publications, 2013), 17.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid, 18.

Ibid, 21.

Ibid, 24.

Ibid, 26.

Ibid, 28.

“The path of great return” is a phrase used in Adi Da’s writings to describe traditional spiritual paths that conceive of Realization in regressive terms.

James Hillman, The Myth of Analysis (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1972), 184.

Carl Jung and Aniella Jaffe, Memories, Dreams, and Reflections (New York: Vintage Books), 188.

Wilber and Hillman share similar influences in the evolutionary ideas of Bergson and Chardin but even more prominently in the Socratic, Platonic and Neoplatonic tradition of the Greeks. Despite these shared foundations, their philosophies reach markedly different conclusions.

Hillman’s usage of “imaginal” is drawn from Henry Corbin’s mundus imaginalis. See Corbin’s “Mundus Imaginalis or the Imaginal World”.

Wilber’s view hides misogyny behind nuance and its primary objective is to place feminism (and its movements) into appropriate “quadrants”. Wilber does not accept patriarchy or the fact that women were historically repressed by men. In an interview with Mary Daly, Wilber’s essay was quoted in a question:

Q: Some people say that exclusively blaming men for the patriarchy is misguided. Transpersonal theorist Ken Wilber, in an article entitled "Don't Blame Men for the Patriarchy," writes: "'Patriarchy' is a word that is always pronounced with scorn and disgust. The obvious and naïve solution is to simply say that men imposed the patriarchy on women. But alas, it is nowhere near that simple. . . . If we take the standard response—that the patriarchy was imposed on women by a bunch of sadistic and power-hungry men—then we are locked into two inescapable definitions of men and women. Namely, men are pigs and women are sheep. . . . But men are simply not that piggy, and women not that sheepy. One of the things I try to do . . . is to trace out the hidden power that women have had and that influenced and cocreated the various cultural structures throughout history, including patriarchy. Among other things, this releases men from being defined as total schmucks and releases women from being defined as duped, brainwashed and herded."

MD: Usually for someone at that state of consciousness—which is unconsciousness—if anything would work, it would be to make the analogy with racism. Because that's back where he is in that. It would be like saying, "Well, that this is a racist society is the fault of blacks, too, and you can't just blame white people for a racist society. The others must have collaborated in it." And the fallacies become immediately obvious, don't they, when you speak of that case.

On balance, for an example of how Wilber’s integral theory can be applied to feminism, see Integral Feminism.

This title is a misappropriation of Adi Da’s essay, The Superior Man, first published in Love of the Two-Armed Form (1978). While Deida’s book focuses exclusively on male attainment, Adi Da’s essay is a broader instruction for both men and women.

For a deeper investigation into the links between Romanticism and feminism, see Y. Monojit Singha’s examination in “Rabindranath Tagore and Feminism”.

Adi Da Samraj, “The Pleasure Dome is Organized Water” in Adi Da’s Divine Work at Quandramama Shikahara (Middletown, CA: Dawn Horse Press, 1997).

Adi Da Samraj, The Complete Yoga of Human Emotional-Sexual Life (Middletown, CA: Dawn Horse Press, 2007), 99.

beautifully written, intricate. Makes me want to spend more time with Hillman. And I appreciate the critique of Wilber who can always use some deflating in my opinion.