The Knee of Listening

Avataric Ontology, Nondual Epistemology, and Mythopoetic Hermeneutics in the Spiritual Autobiography of Avatar Adi Da Samraj

This essay examines the spiritual autobiography of Avatar Adi Da Samraj through textual and personal perspectives. The first part of the essay traces the history of The Knee Of Listening, the evolution of its contents over three decades, and how it reflects the organic unfolding of Adi Da’s life and work. The second part of the essay explores the nature of Avatar as mythos and Adi Da’s language as mythopoetic narrative. This essay is informed by my history, both as a devotee and during my tenure as an editor for the Dawn Horse Press from 2009-2023.

Spiritual autobiographies represent a unique genre of literature. Most biographies of Spiritual Masters are written by disciples, whether during or after the lifetime of the Master. Occasionally, Masters write their own autobiography. Some well-known spiritual autobiographies that were influential in the West include Paramahamsa Yogananda’s classic, Autobiography of a Yogi (1946), Chögyam Trungpa’s Born In Tibet (1966), and Swami Muktananda’s Play of Consciousness (1972). To this list, we will add The Knee Of Listening as a remarkable contribution to the genre of spiritual autobiography, sure to become a 20th century classic.

I. An Parabola: Encountering Adi Da

The Knee Of Listening was first published in 1972 with the subtitle, “The Early Life and Radical Spiritual Teachings of Franklin Jones”. The book went through a number of revisions in subsequent years; the latest edition published in 2004 bears the subtitle “The Divine Ordeal Of The Avataric Incarnation Of Conscious Light”. The latest edition significantly expands upon the original publication at 821 pages—600 pages longer than the original page count of 271.1

The second edition of the original publication received a favorable foreword from Alan Watts along with an endorsement in which Watts states, “It looks like we have an Avatar here”2 and “It is obvious from all sorts of subtle details, that he knows what IT’s all about . . . a rare being”. The foreword and endorsement from Alan Watts come nearly a year before his passing in September 1973. The 2004 edition no longer features the foreword by Alan Watts, replaced by an appreciative and scholastic foreword from Jeffrey Kripal, professor of religious studies at Rice University.

In his foreword, Kripal describes his experience of darśana with Adi Da:

My “meeting” with Adi Da took the form of darśana (a traditional Hindu term for the formal “seeing” of a guru or deity, in which the essence of the guru or deity is understood to be communicated to the seer through the act of seeing itself—a kind of ocular communion or visionary sacrament, if you will). The darśana took place in a formal hall of Adi Da’s residence on the grounds of the Mountain Of Attention ashram. The room was filled with devotees chanting and sitting in contemplation. Adi Da himself was sitting in a large chair, directly in the center. He was clearly in a state of ecstasy: his eyes were rolled up, his fingers were forming some sort of mudra (a posture of the fingers and hands traditionally said to convey a particular state of mind or religious state), and he was sweating profusely. I had the distinct sense that he was intending to communicate his state of consciousness directly to all present, and particularly to those who approached him one by one (including me), by the sheer force of his presence, which indeed was quite palpable.

I knelt down, offered a flower in the traditional manner, sat in darśana for a few minutes, and was then ushered out by my hosts. It was over as quickly as it had begun. As it turned out, however, it was hardly over, for whatever was communicated that night did not leave me easily or soon. For days, I felt as if my consciousness had somehow “shifted”, that it had been affected on levels of which I was only vaguely aware. This sense of a “shift” lasted for an entire week, before I returned to my more usual mode of functioning. That occasion of darśana was an encounter, in person, with the same force of being which informs Adi Da’s books, and which you are about to “meet” in The Knee Of Listening.3

In his writings, Adi Da describes darśana as the sacred sighting of the Realizer, emphasizing it as the principal means for spontaneous and direct entry into his enlightened state of consciousness, whether in his physical company or through a photograph4. Darśana is indeed a kind of a “visionary sacrament”, but it is much more than an ocular transmission—it is the tangible spiritual transmission from the Master to the heart and whole body of the devotee.

On this basis, Kripal summarizes his impression of Adi Da’s texts and teaching:

No reader professionally or personally invested in Asian forms of spirituality and concerned about their effective (as opposed to dysfunctional) translation into Western culture can afford to ignore The Knee Of Listening or the larger textual corpus in which it is now placed, that is, Adi Da’s twenty-three Source-Texts.5 In my opinion, this latter total corpus constitutes the most doctrinally thorough, the most philosophically sophisticated, the most culturally challenging, and the most creatively original literature currently available in the English language. Certainly there are even larger canons in Asia, but these are written and expressed in languages (primarily Sanskrit, Tibetan, Chinese, and Japanese) and interpreted in cultural frames that must remain permanently foreign to the contemporary English speaker and reader. What sets the twenty-three Source-Texts apart is the fact that they were written in English, and that this English idiom has been enriched by a kind of hybridized English-Sanskrit, and that a new type of mystical grammar has been created, embodied most dramatically (and, to the ego, jarringly) in Adi Da’s anti-ego capitalization practice, in which just about every grammatical move is nondualistically endowed with the status once imperially preserved in English for the non-existent “I”. Such a reading experience constantly calls upon one’s ability to think and feel beyond the socially constructed ego.6

Kripal’s portrait of Adi Da’s textual corpus illustrates Adi Da’s teaching not only as a unique dharmic exposition, but as a transcendental imposition on the ego and its limiting paradigms. Adi Da’s texts are imbued with a functional intention: to undermine the ego and speak directly to the heart. Adi Da’s writing is thus difficult to grasp—being at once poetic, authoritative, mystical, philosophical, confessional, scriptural, and revelatory. In the post-modern era of pop spirituality, Adi Da’s writing seem to present an unnecessary challenge and demand, requiring the reader to actually engage with the text as opposed to merely “reading” it intellectually.

The Knee Of Listening began as an autobiographical narrative, but the latest edition features three additional parts that expand on the thirty-two years that have lapsed between these publications. A brief overview of the contents of the 2004 edition of The Knee Of Listening helps us see the breadth of this text:

Part One (“The Knee of Listening”) contains the entirety of the 1972 publication. This is the most accessible part of the text detailing Adi Da’s early-life, his school years at Columbia and Stanford, his “sadhana years” under the tutelage of Swami Rudrananda, Swami Muktananda, and Bhagavan Nityananda, and his “re-awakening” in 1970.

Part Two is a new addition from the 1972 publication—it details Adi Da’s relationship to his spiritual lineage and contains his confessions of being the reincarnation of Ramakrishna-Vivekananda. Part Two also includes Adi Da’s commentary on the teachings of Swami Muktananda and Ramana Maharshi.

Part Three describes two “yogic death” events in Adi Da’s life and their spiritually transformative impacts in his work. This is the most esoteric part of the text and will challenge readers who are unfamiliar with embodied spiritual transformations.7

Part Four is a single essay that describes the essence of Adi Da’s “Way”, only five pages in length.

The first time I attempted to read The Knee Of Listening, I came away discouraged and devoid of comprehension—still, I was intrigued by Adi Da’s solemnity, authority, and intensity of purpose. I was 16 at the time, and it would be another two years before the living power of Adi Da’s spiritual transmission became fully evident in my life. I found the first pages of The Knee Of Listening to be more of an encounter than a “read”. While I did not yet appreciate the mode and nature of Adi Da’s communication, I was absolutely intrigued with a desire to understand him.

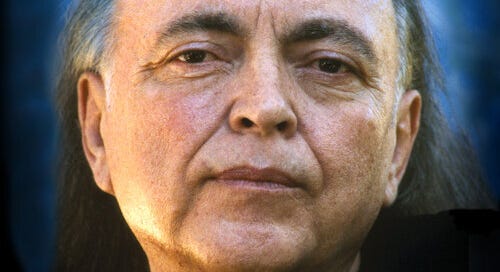

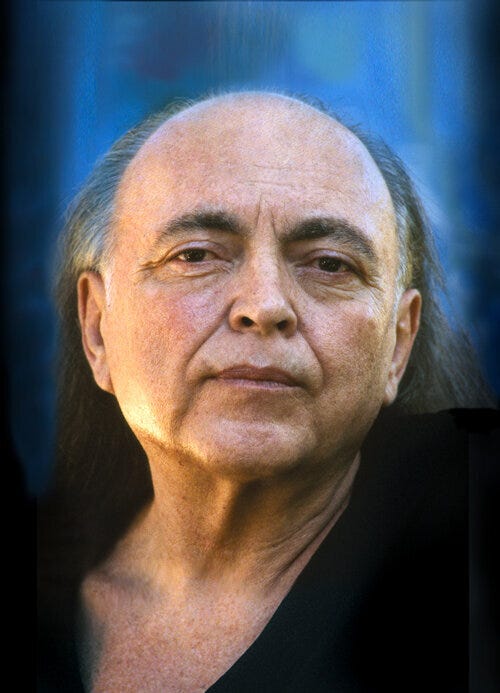

I remember showing my grandfather the 2004 edition, hoping he could help illumine the contents for me. He was a professor of history and remarkably well-read on Indian spirituality and philosophy. When I gave him the book, he glanced at the photo of Adi Da on the cover for a moment and remarked that he knew Adi Da was enlightened by looking at his eyes. The photo on the cover always attracted me, and is the reason why I kept the book by my bedside for two years. I was anticipating a future engagement.

II. Expansions and Editions: 1972 to 2004

There is always a lion at the gate of esoteric knowledge. These “lions” are not only guardians of truth, they can also be the demons of ignorance preventing access to deeper truths. In the case of Adi Da, attempts to understand his life and work routinely raise more questions than answers. Nonetheless, Adi Da addresses these questions directly and indirectly in his disclosures about the paradoxical, contradictory, and incomprehensible nature of his work.

The purpose of this essay is not to compare editions, but such comparisons are inevitable in any honest examination of Adi Da’s impressive, complex, and comprehensive oeuvre. The considerable expansion of the original text—alongside Adi Da’s many name changes and progressive establishment of Avatarhood—challenges literary, biographical, and spiritual conventions of every kind.

First, the literary issues: while revised editions of a text are normative, the significant expansion and even re-casting of one’s own autobiography is unusual. It leads us to ask, how did Franklin Jones become Adi Da? What is the “Avataric Incarnation of Conscious Light” and why are these appellations absent from the original text? Why did Alan Watts refer to Adi Da as an Avatar nearly 30 years before Adi Da ever used that description for himself? What comprises the additional 600 pages of The Knee Of Listening?

These questions point to an issue in the larger trend of Adi Da’s life and work: the nature of his teaching as a spontaneous and progressive unfolding in direct relationship to devotees. According to Adi Da, his teaching was generated from the point of view of Divine Enlightenment, without any egoically superimposed preconceptions. If Adi Da felt devotees were not understanding something, he would state it differently. If he felt devotees were misusing a practice he had given, he would remove it entirely or offer an elaboration on the nature of authentic practice. Thus, Adi Da’s philosophical and spiritual doctrines were established over time, at times apparently contradicting earlier teachings. The ever-changing shape of Adi Da’s doctrine is reflected in his frequent name changes, the numerous changes in naming of his church and tradition, and even Adi Da’s dramatically shifting physical appearance throughout the decades of his teaching-work. Adi Da’s life and work was truly experimental, but by no means inconclusive. In fact, his later textual works8 reflect a definitive doctrine and practice, the conclusions of a thirty-year ordeal of teaching.

The epilogue to The Knee Of Listening, originally titled, “The Man of Radical Understanding” contains one of the keys to understanding Adi Da. An expanded version of this essay is produced in the 2004 edition, with the amended title “I Am the One and Only Man of Radical Understanding”. In this essay, Adi Da describes his nature as a shape-shifter:

The Man of “Radical” Understanding requires no persistent expression, but His manner changes in every circumstance. His understanding adapts to the habit of every appearance. He adopts no visibility that persists. Moment to moment, He cannot be found apart—for, when Truth is Known, the One Who Knows It is unknown (or become Transparent in the Spiritually “Bright” Divine Heart).9

“Understanding” has a profound and technical meaning in Adi Da’s language—it is not merely an intellectual insight or the result of logical reasoning. Adi Da introduced this paradigm in his first public discourse of the same name, “Understanding”. Given in 1972 in Hollywood, CA, Adi Da presented “radical understanding” as a spiritual “re-cognition” into the nature of the ego as an unconscious activity of “self-contraction”.10 Upon understanding that the ego and its sufferings are entirely self-caused, one regains conscious control of the root-mechanism of self-contraction. One of Adi Da’s principal criticisms is the futility of seeking for Realization, because the Condition to be Realized is “always already the case”. Thus, Adi Da’s dharma on “understanding” is a clue regarding the level of comprehension he is asking from readers—a trans-rational and tacit recognition of Reality Itself.

The 2004 edition of The Knee of Listening expands with narratives of Adi Da’s life after 1972, especially regarding the “Yogic death events” of 1986 and 2000. These two events are given considerable import and include devotee testimonies (or leela). These three additional parts focus on Adi Da’s nature as Divine Avatar, progressively revealed in the form of his embodied spiritual transformations that function as ever-magnifying expressions of Realization. In this regard, the visionary sacrament of darśana was given increasing levels of importance in Adi Da’s teaching. Further, Adi Da’s spiritual transformations not only effected changes in his physical body, but profoundly influenced the nature and course of his work and teaching.

Adi Da describes his body as being spiritually transfigured by Divine Self-Realization, which he describes as the “enlightenment of the whole body”.11 As such, his body became the incarnate means for the same transformations to be effected in his devotees. This reflects the traditional understanding that by meditating on the Guru, the Guru’s realization is duplicated in the devotee through a process of spiritual transmission (or shaktipat)—or, stated simply, “you become what you meditate on”. Adi Da asserts that this principle of spiritual transmission and duplication continues even after his lifetime, and that a fundamental purpose of his birth was to establish the means (which he terms “agency”) for this spiritual process to be enacted and fulfilled as long as beings exist. The principal form of agency is Adi Da’s Adi Da’s body itself, ritually erected in life-size photographs and statues, upon which devotees express sacramental worship and practice meditation. This is also why all editions of The Knee Of Listening have featured prominent and striking photographs of Adi Da.12

The most significant difference between the original publication of the The Knee of Listening and the 2004 edition is Adi Da’s presentation of himself as Avatar—no longer only the “Guru” of the original publication or the “Siddha” of the following publications. However, the original text discusses the spiritual process as one of Guru-devotion and satsanga,13 alongside many other themes that remained a consistent cornerstone throughout Adi Da’s teaching.

The fact that Adi Da’s teaching evolved and even seemed to clarify itself over time is used by critics as an argument against Adi Da’s confessions of Avatarhood. However, this argument suffers from idealism in regards to Avatars and Realizers in general—particularly that (1) a Realizer’s teaching simply comes out of them in perfect summary form without further revision and (2) that a truly Realized being is omniscient and therefore never has to revise, clarify, or adjust teachings and that (3) Avatars are not human and therefore do not reflect the embodied realities of being human. At the root of these concerns is a failure to recognize the thoroughly esoteric nature and mythic function of Avatar.14 Therefore, the decoupling of these ideas is essential to understand Adi Da’s Avataric ontology, non-dual epistemology, and mythopoetic hermeneutic.

III. Autobiography or Autohagiography

Critics have referred to the later edition of The Knee Of Listening as a “hagiography”, claiming that Adi Da’s autobiographical narrative has become mythologized and embedded into a claim of exclusive Avataric authority. Lowe is one such critic who writes:

In later editions, Jones' childhood is presented as utterly exceptional...It is clear that Jones' autobiography might best be understood as a kind of auto-hagiography, since its purpose is to preserve for posterity a sanitized, mythologized, and highly selective account of Jones' life and spiritual adventures.15

Lowe’s critique was published in 1996, so we assume he is referring to the 1995 edition which already featured some of the expansions discussed earlier. Lowe uses the term “auto-hagiography” as a pejorative, implying illegitimacy and fabrication, whereas an autobiography should by conventional literary standards represent the “facts”. The intensely metaphysical nature of Adi Da’s life and teaching already challenges established notions of an autobiography—stretching the boundaries of fact and of fiction. For example, Adi Da asserts that Franklin Jones was a “fictional character”, a persona that he consciously assumed the identity of in order to teach human beings.16 Does this make his autobiography real or imaginary, factual or fictitious? When, how, and why did Franklin Jones become Adi Da? The Knee Of Listening thus exhibits a paradoxical ontological status only because its subject does.

Hagiography, being an established genre of religious literature since antiquity, is a biographical portrayal of a religious figure. Written by disciples, and essentially emic (or “insider”) in perspective, hagiographical accounts are viewed critically in modern times because they lack “objectivity”. However, the function of hagiography is not to establish objective facts. Rather, hagiography intentionally indulges in embellishment as a mythopoetic device in order to illustrate the transpersonal qualities of the subject and to evoke a meaningful response in the reader. In India, spiritual biographies of a Master are almost always hagiographical in nature. Tibetan Buddhism has an extensive hagiographical genre known as nam thar, in which the lives of famous Masters are described by close disciples, and where mythical embellishment is accepted as a literary device for expressing the metaphysical qualities of a Master and their Realization.

The 2004 edition of The Knee Of Listening does contain narratives from devotees, but these narratives are clearly indicated as such and only form a small portion of the text, a far cry from a hagiographical account of Adi Da’s life. Furthermore, to my knowledge, no Master has ever written their own hagiography. This raises the question of whether an autobiography can be a hagiography—it does seem possible (though unusual) in theory. The primary motivation of Adi Da’s autobiographical expansion, as reflected in its contents, is to provide an account of Adi Da’s life and work at the turn of the millennium, since the original text was written at the very outset of Adi Da’s role as a teacher. The expanded edition now accounts for radical changes and evolutions in Adi Da’s life and teaching, where the original text reads more like a traditional autobiography. Therefore, the critical issue is not an argument on the nature of the text itself, but everything the text suggests, implies, and directly states. Critics are not upset that The Knee Of Listening fails to conform to their autobiographical expectations—they are upset with the contents, the message, the person.

To clarify confusion, Adi Da opens his 2004 autobiography with what he calls a “First Word”, titled, “Do Not Misunderstand Me”. In this essay, he attempts to deconstruct the common misconceptions about his teaching and status, while criticizing the tendency toward cultism. In one such passage, Adi Da writes:

I do not tolerate the so-called “cultic” (or ego-made, and ego-reinforcing) approach to Me. I do not tolerate the seeking ego’s “cult” of the “man in the middle”. I am not a self-deluded ego-man—making much of himself, and looking to include everyone-and-everything around himself for the sake of social and political power. To be the “man in the middle” is to be in a Man-made trap, an absurd mummery of “cultic” devices that enshrines and perpetuates the ego-“I” in one and all. Therefore, I do not make or tolerate the religion-making “cult” of ego-Man. I do not tolerate the inevitable abuses of religion, of Spirituality, of Truth Itself, and of My Own Person (even in bodily human Form), that are made (in endless blows and mockeries) by ego-based mankind when the Great Esoteric Truth of devotion to the Adept-Realizer is not rightly understood and rightly practiced.17

This passage is one of countless such passages in Adi Da’s literature criticizing the cultic tendency in human beings, positing cult-making as the inevitable act of ego-possessed individuals, and differentiating it from the authentic Guru-devotee pedagogy. He defends against criticisms that his confessions of Avataric status are a form of self-delusion and aggrandizement and disavows the notion of being a cult leader, which he describes as the scapegoat ritual of the “man in the middle”. Finally, Adi Da affirms the great tradition of Guru devotion as the ancient and esoteric means for Realization while calling for a right understanding and living practice of it. Five paragraphs later, Adi Da gives another admonishment:

Therefore, no one should misunderstand Me. By Avatarically Revealing and Confessing My Divine Status to one and all (and All), I am not indulging in self-appointment, or in illusions of grandiose Divinity. I am not claiming the “Status” of the “Creator-God” of exoteric (or public, and social, and idealistically pious) religion. Rather, by Standing Firm in the Divine Position (As I Am)—and (Thus and Thereby) Refusing to be approached as a mere man, or as a “cult”-figure, or as a “cult”-leader, or to be in any sense defined (and, thereby, trapped, and abused, or mocked) as the “man in the middle”—I Am Demonstrating the Most Perfect Fulfillment (and the Most Perfect Integrity, and the Most Perfect Fullness) of the Esoteric (and Most Perfectly Non-Dual) Realization and Reality.18

Thus, Adi Da establishes a thoroughly esoteric definition of Avatarhood, decoupling it from notions of the Judeo-Christian Creator-God, and paradoxically affirming his “Divine Status” as ontologically non-dual. In particular, Adi Da differentiates the positive sacrifice of the Avatar from the negative sacrifice of the scapegoat ritual. While this passage may be less than satisfying for Adi Da’s critics, who see his claims as nothing more than megalomania and subsequent cultism, I believe an esoteric and even imaginative understanding of Adi Da’s Avataric status is the key to unlocking a greater understanding. The puzzles Adi Da presents in his teaching are not riddles to be resolved, but transcendental koans, made for puzzlement, until awakening.

IV. Avataric Mythopoesis: Fictional Character and Divine Person

Adi Da described “Franklin Jones” as a “fictional character”, and in doing so, universally extended a profound criticism of egoity. In our self-defining identities, we are all kinds of fictional characters revolving around a presumed identity, whirling in a masked mummery. In psychoanalytical thought, the “persona” is an identity worn as an unconscious compensation. “Persona” comes from mid-18th century Latin, literally meaning “mask” and “character played by an actor”. Adi Da refers to egoic life as masked play-acting that he calls “mummery”. A “mummer” is a pantomime, an actor in a masked mime. A “mummery” is a performance by mummers, a “ridiculous ceremonial”.

The individual, separate and separative life is an imagination—a reflection in the pond of Narcissus. Yet, the water itself remains to be recognized, as it is. Adi Da described how his function as Guru was to “stir the pond” so that Narcissus would awaken from a self-reflected life. The reflecting pond is a poetic image that describes the ego and the nature of Reality. Adi Da’s writings prominently display mythic ideas as an image of spiritual concern, from the myths of Oedipus and Narcissus to the mythopoesis of Avatar.

The Bhagavad Gita states that an Avatar is born to restore righteousness in the dark time, when the world is consumed by spiritual ignorance. The Avataric concept is elaborated in Hindu mythology, which describes ten such incarnations of the Divine. The first three are non-human—a fish (matsya), a turtle (kurma), and a boar (varaha). The next three Avatars become increasingly human—a half-man / half-lion (narasimha), a dwarf (vamana), a warrior (parashurama). The seventh, eighth, and ninth Avatars are largely regarded as historical persons with associated mythologies—Rama (the King of Ayodhya and subject of Ramayana), Krishna (source of Vaishnavism whose life story is told in Krishna Leela), and Gautama Buddha (the historical Sakyamuni Buddha). The tenth Avatar is known as “Kalki” and is prophesied as a future appearance.19

Avatar has always been a myth and all Avatars have their mythologies. Adi Da placed himself within the Avataric mythologem, and in doing so he employed the age-old hermeneutic of mythopoesis. The question is no longer whether we accept Adi Da as an historical Avatar, or whether his claims are factual or fictional—but whether we can imagine an Avataric archetype appearing within the dream.

In one passage, Adi Da describes the world as an unconscious dream-image in which the Avatar appears:

The “world” does not want to be Awakened.

Does the dreamer ever try to awaken anyone or everyone in his or her dreams?

It does not occur to the dreamer to do so.

Those who appear in dreams are not there to be awakened . . .

[The world] is the manifestation of sleep.

It is unconscious . . .

The “world”, in all of its wanting to persist, is not entirely wanting the Divine Avatar to Appear, and, Thus, to Awaken all-and-All from the dreaming sleep of Being.

Nevertheless, I Am here.20

Adi Da sees the world of ego-bound humanity as a manifestation of unconsciousness, a dream-like illusion. As the Divine Avatar, he appears within the illusion to awaken the dreamer from sleep. As Jung clearly established, the images of dreams are mythic symbols. The “Divine Avatar” is precisely such a mythopoetic symbol, a mirage of Truth in a spiritual desert, a watery palindrome of Reality Itself.

Mythopoesis, or the act of creating a mythology, has occupied humans since time immemorial. J.R.R. Tolken is credited with re-introducing the device in the 1930s. Tolkien’s work is a clear example of modern myth-making. He not only wrote fantasy novels, but mapped mythic worlds complete with languages. Chögyam Trungpa is said to have referred to Tolkien’s work as a form of terma, a word that literally means “hidden treasure”. Terma forms an important category of revealed teachings in Tibetan Buddhism, where a treasure-revealer (tertön) discovers hidden teachings in dreams and spiritual states of consciousness.21 Terma is a form of mythology, a teaching-language constructed from the symbolic world of dreams and transpersonal states of being. Dharma as terma is thus one example of a mythopoetic hermeneutic in spiritual teachings.

Adi Da’s teaching functions as terma in the sense of being an esoteric revelation that is “Avatarically Self-Revealed”. Adi Da’s writing is thus infused with its own mythopoetic conventions—a “hybridized Sanskrit-English grammar” with “anti-ego capitalization” and an unconventional use of punctuation. His non-ordinary speech is grounded in his non-dual identity and criticism of egoic communication:

Ordinary speech and written language are a “theatrically”-conceived mode of communication, which (as such) is “played” upon the “fiction” of an ego-“I” . . .22

In criticizing ordinary speech, Adi Da asserts his linguistic conventions as an intentional undermining of egoity—employing a hermeneutical structure that revolves around the centerpole of Reality, rather than the fiction of egoity. This is accomplished within a mythopoetic narrative that employs word as image. As Adi Da writes, “I Spontaneously Uttered the ‘Picture’ that is My every ‘Source-Text’”.23 He elaborates how his capitalization schema functions as intentional imaging:

The uppercase Written Words Represent (or Picture) the Reality-Truth of Heart-Significance—and the lowercase words, by comparison, characteristically achieve significance as indicators (or representations, or pictures) of conditional (or limited) existence.24

Image is the sign and symbol of myth, and myth is the language of spirituality. That which transcends the conventions of rational conceptualization cannot be adequately rendered in conceptual thought, but it can be seen. Thus, Adi Da’s writing also functions as a visionary sacrament, a mythological image that points to itself in transcendental realism.

Adi Da’s writing is deeply self-referential. He refers to himself with the pronouns “My” and “Me” (always capitalized) and discusses his own texts within texts. There is an intricate weaving of the textual corpus within itself, with large portions of shared essays featured across texts. Aside from organizing and structuring his corpus, Adi Da made great effort to reveal his nature, qualities, process, and intentions in considerable detail. Adi Da’s usage of the pronouns “My” and “Me” is perhaps the most “offensive” part of his writing to those unacquainted with his esoteric hermeneutic. His usages appear resonant with the Bhagavad Gita, where Krishna describes himself with the same pronouns, typically capitalized in English translations. Was Adi Da intentionally mirroring the Avataric narrative of the Bhagavad Gita in his own writing? There is good reason to think so, especially when we consider that Adi Da published his own rendering of passages from the Bhagavad Gita in early texts and later re-worked these renderings into an essay he titled, “The Divine Avataric Self-Disclosure”. In using the words “My” and “Me”, Adi Da is not promoting an exaggerated view of himself, rather he is communicating a universal and transpersonal identity, beyond the fiction of “I”. Adi Da also collapses any sense of negative hierarchy when he makes the statement, “I Am you”, making clear that his “identity” is not exclusive or separate but universally identical to the true nature of all.

An autobiography is naturally self-referential, but Adi Da’s autobiography is self-aware in meta-narrative. Self-referentiality is another feature of mythopoesis—its imaging is circular and conscious of itself. Adi Da’s autobiography is precisely of such an uroboric shape—it bends upon itself as the reader ends upon it, drawing a sphere of deepening consideration. Was Adi Da intentionally crafting a self-referential mythology or was he using the conventions of mythology to reveal a universal truth? Adi Da was well-read in the works of C.G. Jung25 and Joseph Campbell, and even wrote a commentary on Campbell’s presentation of myth26 titled “Myth is a Call to Ecstasy”. In this essay, Adi Da describes the sacred nature and function of myth:

Mythology (like art, ritual, philosophy, and the techniques of ecstasy) is one of the primary languages of religion (or of sacred culture, in the broadest sense). And the (inherently sacred) function of mythology is to “picture” (rather than to “explain”) the Great Means, the methods (or techniques), the processes, the stages, the obstacles (or tests), the Helping encounters, the intermediary goals, and the Ultimate Goal of the religious Quest (or the sacred Way).27

If myth pictures the sacred, then mythopoesis is the natural hermeneutic of spiritual literature. Adi Da differentiates between image-making and explanation, placing myth in the realm of imagination, not logic. Such notions have been passionately echoed by the Romantics who swooned in the imaginal world of myth and meter.

Adi Da continues his commentary:

Mythology is one of the languages of ecstasy. Therefore, the statements (or propositions) of mythology (and even of religious and Spiritual philosophy) are not (if properly understood) mere statements of fact (or of universal and, as mere matters of fact, always the case “truths”). Rather, they are ecstatic Revelations, or expressions of a state of Realization that (if actually Realized) presently transcends the world, the body, and much (or, in the Ultimate case, even all) of mind.28

The word “myth” comes from the Greek mythos, literally meaning “utterance”. In an essay describing his textual hermeneutics, Adi Da uses the word “utterance” four times:

The “Source-Texts of My Direct Self-Utterance are the Always-Living Word of Reality Itself . . .

The “Source-Texts” of My Divine Avataric Word are . . . the Always Direct and Non-mediated Self-Utterance of My Real Person . . .

[My Divine Avataric Word] Is The Direct Self-Utterance of Reality Itself . . .

My Divine Avataric Word of Direct Self-Utterance is Spoken from the . . . Perfect Self-Position of Reality Itself . . . .29

In the “Boundless Self-Confession”, Adi Da uses the word “Utterance” again in the hybridized phrase “Revelation-Utterances” and in reference to his art as “Transcendental Realist Utterances”. Furthermore, Adi Da cast his entire person into mythos when he stated, “I Am Simply the Utterance of the ‘Bright’”.30

The Roman historian Sallust said, “Myths are things that never happened but always are”. If we approach The Knee Of Listening as a mythopoetic narrative rather than a compilation of biographical “facts”, then we unlock the power and sacred meaning of its communication. We will also see it differently—not as mere words to be logically assimilated, but images and pictures to be visioned, a transmission to be felt, ecstasy to be experienced. Thus, “Franklin Jones” becomes a fiction of character and “Adi Da” the reality of Divine Person.

V. Rites of Transmission

Adi Da’s life and teaching calls for an esoteric and spiritually-awakened form of understanding that transcends rational, binary, and linear modes of comprehension. He says, “The Great Statements and Myths can be properly ‘understood’ only in ecstasy (or Samadhi).” In other words, our understanding of Adi Da and our appreciation of his mythos requires a transformation of view and genuine Communion.

Spiritual texts are coded communications that require initiatory rites of transmission to be rightly understood. In the Tibetan tradition, texts are recited aloud by teachers. Constituting an “oral transmission” (rlung) of the practice they describe, recitation is considered necessary for the growth and fruition of the practice. Adi Da’s texts function as agency of themselves, it is self-transmitted to the reader who participates in it. Therefore, the open-minded study of Adi Da’s teaching has the potential to become an initiatory rite of transmission.

The Knee Of Listening came to life for me one evening after a spiritual experience that I later came to recognize as Adi Da’s spiritual transmission. After this ecstatic experience of love and bliss, I decided to open the The Knee Of Listening to a random page, hoping to understand it once and for all. I opened to a passage that read:

Love-Bliss is simply Perfect Presence,

for Reality is That Which is Unqualifiedly Present.

Present Reality is Conscious As Love-Bliss.31

The words spoke directly to my experience, and transmitted it again. I began to feel a living force in Adi Da’s words, a relational energy that felt conscious and intimate. I felt somehow seen and known by this force, and I soon discovered, able to engage with it. I came to know this force through its observable characteristics and pattern of movement—like a pressure above the head that blissfully descended into the body, filling the heart with “Love-Bliss” and the body with a felt-quality of Light. I could breathe it and become dissolved in it—and this force emanated from Adi Da’s words, photos, and videos. Later that year, I was able to sit with Adi Da through a live darshan occasion broadcasted through the internet, and all my experiences of his transmission were confirmed and deepened.

This is not to suggest that such experiences are somehow necessary to read The Knee Of Listening. But it is to point out how initiatory transmission can unveil a previously coded comprehension. This is the mystery of engaging with Adi Da’s texts, as a reading of his words is an encounter with his person, and it unfolds according to its own laws. For every person, it will be different, unique, unpredictable. Adi Da says he is perpetually engaged in an “eternal conversation” with everyone who receives his words. This invitation to spiritual intimacy is fundamental to Adi Da’s work—as he summarily stated in his earliest talks: “I offer you a relationship, not a technique”.

Thus, The Knee Of Listening is more than an autobiography, hagiography, or mythic narrative, even while it employs all of these conventions. The Knee Of Listening is a living communication that asks to be felt in the quiet spaces beyond reason, to be seen with the eye of spirit, to be heard with the ear of the heart.

As Aldous Huxley wrote in The Perennial Philosophy:

The Logos passes out of eternity into time for no other purpose than to assist the beings, whose bodily form he takes, to pass out of time to eternity. If the Avatar’s appearance upon the stage of history is enormously important, this is due to the fact that by his teaching he points out, and by his being a channel of grace and divine power he actually is, the means by which human beings may transcend the limitations of history.32

This larger edition was closer to the original manuscript, which was roughly twice the size of the 1972 publication before being abridged at the suggestion of publishers and editors.

The story behind this comment from Watts is as follows: “Alan Watts. Not a man to be caught with his comments out on a limb, he wrote a carefully worded foreword to The Knee of Listening which would leave him unbesmirched if Bubba (Adi Da) subsequently turned out to be a charlatan. However, a year later, when he was invited to contribute a foreword to The Method of the Siddhas, he had an opportunity to study Bubba on videotape. The encounter left him shaken and in tears overwhelmed by the gestures, voice, and humor of what he felt was an obvious godman. “It looks like we have an avatar here,” Watts is said to have commented. I can’t believe it, he is really here. I’ve been waiting for such a one all my life.” From https://beezone.com/adida/forward.html.

Adi Da Samraj, The Knee Of Listening (Middletown, CA: Dawn Horse Press, 2004). xii - xiv.

Adi Da viewed darshan as an eternal possibility that was not restricted to being in his physical company, but that would occur after his lifetime primarily through photographs but also through video. A significant aspect of Adi Da’s purpose was to establish such means (which he called “agency”) through which his spiritual transmission could be tangibly perceived in future generations.

At the time Kripal’s foreword was published, Adi Da had organized his textual corpus into the “23 Source-Texts”. In later years and amidst a notable expansion of his literature, Adi Da re-organized the structural schema of texts from 23 Source-Texts to “23 Courses”. Each course contains multiple texts. Here, the word “course” has the intentional double-meaning of a path of study and a “stream” of knowledge.

Adi Da Samraj. The Knee Of Listening (Middletown, CA: Dawn Horse Press, 2004). xiv - xv.

For an exploration of embodied spiritual transformations in both Christianity and Tibetan Buddhism, see Francis Tiso’s Rainbow Body and Resurrection (2016).

See The Aletheon, The Gnosticon, The Pneumaton, Transcendental Realism, and Not-Two Is Peace.

Adi Da Samraj. The Knee Of Listening (Middletown, CA: Dawn Horse Press, 2004). 410.

See The Method of the Siddhas (1973) and/or its later publication as My Bright Word (2005). “Understanding” is the opening talk of both editions.

See The Enlightenment of the Whole Body (1978).

Adi Da refers to his photographs as mūrti, a Sanskrit word that means “form, embodiment, shape, deity”. In doing so, Adi Da was establishing a formal function for his images as esoteric iconography. As he said, “I Am the Eternally Living Murti”. At the same time, Adi Da was critical of idolatry, stating that his mūrti should not be used as a “substitute” for him, and further establishing mūrti as a symbolic but spiritually effective agent of transmission.

In later writings, Adi Da mostly avoided this term for its traditional implications, favoring English renderings instead—most commonly “Communion” and “Company”.

The mythology of the Avatar (in the East) and Incarnation (in the West) is explored by Geoffrey Parinder in Avatar and Incarnation (1970).

Scott Lowe and David Lane, "Da: The Strange Case of Franklin Jones" (Walnut CA: Mt. San Antonio College, 1996).

In 1974, Adi Da comments on his birth name “Franklin Jones” as a consciously assumed persona: “I entered into this plane of life with . . . and took hold of a psycho-physical form which in itself is no more illuminating than any other psycho-physical form. It needed to be transformed. That transformation could have taken place in any number of ways. The way that I chose to do it was through this peculiar adventure of Franklin Jones. All the kinds of things that can be said about Franklin Jones are secondary, they’re not real in the absolute sense, they are episodes in the persona, which is in fact how everybody else lives, except they don’t do it consciously”. From https://beezone.com/2main_shelf/index-19.html

Adi Da Samraj, The Knee Of Listening (Middletown, CA: Dawn Horse Press, 2004). 15.

Ibid, 16-17.

In the early 90s, Adi Da described himself as the “Kalki Avatar”, but later retracted this descriptor, which he felt was too constrained to the Hindu tradition in particular. It is notable, however, that Kalki is described as a riding a white horse. The “dawn horse” is a recurring archetype in Adi Da’s life and work, with a white winged horse first appearing on Adi Da’s magnum opus The Dawn Horse Testament.

Adi Da Samraj, “The Boundless Self-Confession” (Middletown, CA: Dawn Horse Press, 2009). 150.

The relationship between Tolkien and the Tibetan terma tradition is further explored by Erik Jampa Anderson in “With Furious Speed: Tolkien, Revelation, and the Tibetan Treasure Tradition”.

Adi Da Samraj, The Aletheon (Middletown, CA: Dawn Horse Press, 2009). 39.

Ibid.

Ibid, 41.

Adi Da comments on Jung in first part of The Knee Of Listening, see 76-97.

The essay was written in response to an interview with Joseph Campbell conducted by Jeffrey Mishlove, titled “Understanding Mythology”.

Ibid.

Adi Da Samraj, The Aletheon (Middletown, CA: Dawn Horse Press, 2009). 37-41.

Adi Da Samraj, The Boundless Self-Confession (Middletown, CA: Dawn Horse Press, 2009). 113-160. The “Bright” is Adi Da’s term for the Self-Radiant nature of Reality, as described in The Knee Of Listening (p.26): That Awareness, that Conscious Enjoyment, that Self-Existing and Self-Radiant Space of Infinitely and inherently Free Being, that Shine of inherent Joy Standing in the heart and Expanding from the heart, is the “Bright”. And It is the entire Source of True Humor. It is Reality. It is not separate from anything.

Adi Da Samraj, The Knee Of Listening (Middletown, CA: Dawn Horse Press, 2004). 408.

Aldous Huxley, The Perennial Philosophy. 1st Harper Colophon ed. (New York: Harper & Row, 1970). 51.