“Spirits of the Unconscious” was written as my graduate thesis at Middle Way Acupuncture Institute. The text is presented here without revisions, but the formatting has been adapted for the Substack medium. Those who wish to read the thesis as a PDF in APA formatting can do so here: Spirits of the Unconscious. Given the significant length of this treatise, I cannot say which format is easier to read (PDF or Substack). I personally find APA formatting harder to read (especially because of my tendency to intersperse block quotations throughout the main text). Therefore, I have presented the entire treatise here in usual essay formatting, complete with tables, endnotes, references, and appendices.

The essay is structured in four parts. Below, I give an overview of each part, followed by the table of contents. I hope this aids the reader in navigating the length and structure of the argument.

As always, thank you for reading!

—Neeshee Pandit

Overview

My thesis examines the meaning of “possession” in Chinese medicine, Freudian and Jungian psychology, and the Worsley school of five-element acupuncture. I examine the meaning of “psyche” in psychology and acupuncture and ultimately posit acupuncture treatment as a form of psychotherapy.

In Part One, “Demons Dragons, and Ghosts”, I trace the history of demonology in Chinese medicine, the philosophical transition from early shamanism to Han-dynasty naturalism, and the origins of acupuncture in exorcism.

In Part Two, “Acupuncture and Psychoanalysis”, I explore the relationship between acupuncture and psychoanalysis, Freudian and Jungian interpretations of possession, and the nature of acupuncture as a psychological therapy.

Part Three, “Possession in Five-Element Acupuncture”, represents the core of the thesis. Here, I outline my theory of acupuncture as psychotherapy, meridians as the somatic unconscious, and treatment as an alchemical event. I then proceed to give a clinical portrait of possession—its etiology, diagnosis, pathogenesis, and treatment. I explore treatment as exorcism, the practitioner as shaman, and the meaning of resurrection. This section closely examines the revival of possession treatment by J.R. Worsley and its clinical applications.

Part Four concludes with a reflection on demon vs. daemon, the nature of character and calling, and the role of acupuncture in the vale of soul-making.

Table of Contents

I. Demons, Dragons, and Ghosts: A Brief History of Demonology in Chinese Medicine

Demonology and Systematic Correspondences

From Demons to Nature

Possession as Parasitism

II. Acupuncture and Psychoanalysis

Possession, Superego, and Western Psychiatric Disorders

Spirit and Psyche

Anima/Animus

Possession as Complex

III. Possession in Five-Element Acupuncture

Possession and the Somatic Unconscious

Definition and Etiology

Diagnosis and Pathogenesis

Treatment: Seven Devils, Seven Dragons

Treatment as Exorcism

Possession as Obsession

Instrumentality: Practitioner as Medium

Internal Dragons

External Dragons

Soul-Loss and Resurrection

IV. Demon or Daemon: The Vale of Soul-Making

NOTE: J.R. Worsley’s influence on my views is obvious. My intention has been to honor and positively explore his teachings (alongside those of Freud, Jung, Hillman, and others) while adding creative insights of my own. Thus, the views presented here are entirely my own and do not—necessarily or officially—reflect the views of J.R. Worsley, the Worsley Institute, or the Worsley lineage.

I. Demons, Dragons, and Ghosts:

A Brief History of Demonology in Chinese Medicine

The belief in spirits stems from the indigenous worldview of an animated world, where the boundaries between dreams and waking reality are fluidly perceived. Spirit-possession and soul-loss are perhaps the original pathologies imagined by human beings for which a healing intervention was needed. Shamanism was the original form of therapeutic concern, expressed as a need for protection (or “immunity”) from invasive influences.

In Chinese medicine, invasive pathogenic factors are examined with a multidimensional phenomenology. The human being is composed of physical, mental, and spiritual levels of existence. Thus, invasive pathogenic factors are seen on a spiritual level as spirit-possession and soul-loss; on a mental level as astrological factors; and on a physical level as climatic factors, parasites, and communicable diseases.

Interest in the treatment of possession pathologies has been rekindled throughout the history of Chinese medicine, both at home and abroad. In the seventh century, Sun Simiao (ca. 581 – 682 CE) resurrected Zhou dynasty notions of demonological disease with herbal prescriptions and acupuncture protocols. By the twentieth century, Chinese medical notions of possession had mingled with European thinking, especially the tradition of psychoanalysis. Possession was notably re-imagined by J.R. Worsley (1972 – 2003 CE), who interpreted the illness in psychological terms as a loss of agency and taught two acupuncture protocols for its treatment.

As a concept, possession represents the nexus of culture and medicine, where a cultural notion is sublimated into a medical concept. A medical understanding of possession must attend to its cultural context while viewing possession with the pathologized eye of the profession. In order to understand possession, we have to examine multiple disciplines—animism, shamanism, demonology, anthropology, and psychology.

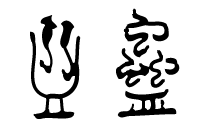

Possession has been a central concern of medicine since antiquity. The Chinese term for medicine, yi, has etymological links to possession. This linguistic link reveals that possession has been a central concern of medical practice since antiquity. Through analyzing the characters in yi, Jarrett (2005) concludes that it “contains the notion of piercing the skin with arrows similar to piercing the air with lances to chase away the demons.” (p. 39). This interpretation is shared by Unschuld (2010), who also traces the origins of acupuncture to the spears used to drive away demons. The etymological and conceptual link between medicine (yi), possession, and acupuncture is thus well-established in the history of Chinese medicine.

From a medical view, the existence or non-existence of spirits is a peripheral concern because the phenomenon of belief in spirits is consequential in itself. In medicine, we look to interpret the nature of an object based on its subjective value—does it promote health or not? Therefore, while possession may conjure sentiments of antiquated superstition, we will see how these ancient ideas are resurrected in modern acupuncture therapeutics.

Demonology and Systematic Correspondences

Belief in spirits as causative agents of disease dates to the earliest periods of Chinese history. According to Harper (1998), “The idea that demons and the spirits of the dead sicken the living is in evidence in the earliest Chinese written records, the Shang inscriptions on bone and turtle shell (ca. thirteenth to eleventh century B.C.)”. (p. 69). Naturalistic notions of health and disease from the Han dynasty classics eventually replaced the etiology of demons. However, the idea that health is dependent on exogenous entities (whether spirits or climatic factors) persists throughout Chinese medical history. If demons are the cause of illness, then the nature of illness is a form of a spirit-possession, and the method of treatment is exorcism. Such demonological notions of health existed long before the advent of systematized medicine and meridian theory.

The Shang dynasty was conquered by the Zhou in 1046 BCE. With its nearly eight-hundred-year reign, the Zhou period remains the longest historical epoch of Chinese history. Unschuld characterizes the transition from the Shang to Zhou dynasty as a shift in attitudes toward shamanism—a movement away from ancestor worship and toward demonic spirits. Unschuld (2010) writes that the “belief that demons could cause illness is widely documented in the literature of the later [Zhou] period”. (p. 37). The healers who healed possession were known as wu, a character that depicts two female shamans dancing. Wu were magical healers who used ritual chants, herbal medicines, talismans, and ritual fumigations to exorcise demons. By the first millennium, demonology was evidenced as distinct illnesses attributed to malevolent spirits:

Demonic medicine is based on the beliefs that illness is caused by the actions of evil spirits. Typical views of demonic medicine, present in the literature of the first millennium A.D., are expressed in the following conditions defined as illness: “struck by evil” (chung-o), “assaulted by demons” (kuei-chi), “possessed by the hostile influence of demonic guests (kuei-k’o wu-chi), and “possessed by the hostile” (chu-wu). (Unschuld, 2010, p. 36)

From Demons to Nature

Demonic possession is often misconceived as a pre-medical concept. However, demonic possession has long been part of the systematized nosology of Chinese medicine into the seventeenth century. Harper argues that demonic concepts of illness were re-translated (but not truly replaced) by naturalistic concepts of illness in the Han Dynasty classics. He groups demonic and naturalistic concepts within the broader nosology of “ontological pathology”: an illness that exists in the form of an entity—whether demon, season, element, wind, vapor, heat, cold, etc. (Harper, 1998, p. 69). The pathogen changes, but the concept perseveres through all its guises. Therefore, the root of demonology is not merely a belief in the existence of spirits, but the paradigm of external pathogenic factors.

By the time of the Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), Chinese medical philosophy began to embrace a rational and empirical theory of health and illness that left demonology behind. Unschuld refers to this philosophy as “the theory of systematic correspondences”, which views the human being as a microcosm of the natural world governed by natural laws. Health was no longer freedom from spirit-possession, but a rhythmic synchronization with the cycles of nature, seasonally and astrologically. Calendrical notions of health arose in tandem with agrarianism—health became a matter of “cultivating” the inner landscape of the body, now “irrigated” by a network of channels. Thus, calendrical patterns became circulatory perceptions—health is circulation, disease is blockage.

In the Tang Dynasty (618 – 907 CE), the concept of spirit-possession was revived by the Chinese scholar-physician, Sun Simiao. One of the earliest prescriptions for the fumigation of demons is found in Sun Simiao’s treatise on alchemy, Dan Jin Yao Jue (“Great Secrets of Alchemy”). In a later compendium, the Qian Jin Yi Fang (“Supplement to the Prescriptions Worth a Thousand Gold”), Sun Simiao listed thirty-two herbs regarded as being effective against demons. Unschuld (2010) quotes a passage from Sun Simiao that illustrates his view of illness as a “central thesis of demonic medicine”, in which Sun Simiao expresses the “conviction that illness and suffering are natural and unavoidable”, clearly illustrating the influence of Daoism and Buddhism in Sun Simiao’s worldview. (p. 43). Unschuld argues that Sun Simiao’s view runs counter to the predominating medical theory of the time—the theory of systematic correspondences—which placed the agency of health in individual behavior following natural laws. Unschuld (2010) states that this theory is based on “the belief that illness could be avoided by means of an appropriate way of life”, a point of view that he sees as an extension of Confucianism. (p. 43).

By the Ming Dynasty (1368 – 1644), ritual shamanism conflicted with the dominant philosophy of Confucianism and was thus regionally contained. Despite this tension, we see an overlap of values between shamanism and Confucianism in ancestor worship and filial piety. However, the shamanic focus on the individual remained a critical divergence between Confucian ideals of the collective. During this time, the Ming dynasty physician, Zhang Jiebin, “enumerated demonology as the thirteenth medical specialty in his 1624 work, the Classic of Categories”. (Eckman, 2007, p. 215). Eckman (2007) also notes the tripartite etiological model of Chen Yan (1121 – 1190 CE), a Song dynasty physician who placed demonic possession in a “miscellaneous” category, “meaning it was neither an exogenous nor endogenous cause of disease”. [1] (p. 215).

Possession as Parasitism

The concept of possession has also mingled with the concept of parasitic pathogens.[2] For the Chinese, parasitism is conceived in demonological terms as a “worm spirit” (ku). Fruehauf translates the concept of ku into a syndrome (“Gu syndrome”) encompassing a range of autoimmune pathologies. He approaches Gu syndrome as a “forgotten clinical approach for chronic parasitism.” Fruehauf remarks that Gu syndrome has been “dismissed” and “submerged” in modern clinical practice where it is largely regarded as “superstitious.” However, Fruehauf translates the demonology of Gu syndrome into a modern “clinical approach that may provide an answer to the many invisible ‘demons’ that plague patients in the modern age, namely systemic funguses, parasites, viruses, and other hidden pathogens.” (Fruehauf, 1998).

A “hidden pathogen” is an invisible etiological factor. Earlier, we grouped demonic and naturalistic ideas of illness as “ontological pathologies”—etiological factors as entities. Within this, we can now identify a subcategory—“invisible pathologies”. Demons, wind, and parasites are all invisible pathogens. What is hidden is invisible, and what is invisible is unconscious, a point we will examine later. For now, we can situate the pathology of possession in three forms: (a) an ontological pathology, (b) an invisible pathology, and (3) an unconscious pathology.

Fruehauf re-interprets Gu syndrome in modern terms via a range of physical, neuromuscular, and psychological symptoms: chronic diarrhea, alternating diarrhea and constipation, explosive bowel movements, abdominal bloating, muscle soreness, wandering body pains, cold night sweats, depression, frequent suicidal thoughts, fits of rage, confusion, visual and/or auditory hallucinations, epileptic seizures, and the sensation of “feeling possessed”. Elaborating on the nature of Gu syndrome as a “possession syndrome,” Fruehauf (2008) writes:

I found chronic parasitism reflected in a huge area of classical Chinese medicine that was called Gu zheng, or Gu syndrome, which essentially means “Possession Syndrome”. Gu is a character that is very old, perhaps one of the oldest characters in the Chinese textual record altogether, since it is a hexagram in the Yijing. It is literally the image of three worms in a vessel. This to me is one of those strokes of brilliance that you find in the symbolism of the ancient Chinese—that they recognized 3000 years ago that chronic parasitism can cause psychotic or psychological symptoms. Because of the psychological, emotional, and perhaps spiritual implications of this term, Gu, when the Chinese standardized the classical record for the much simplified barefoot doctor approach of the TCM system in the 1950’s, they threw out lots of complicated and ideologically problematic topics, and obviously this “Possession Syndrome” was one of the first ones to go.

While he associates Gu syndrome with chronic parasitism, Fruehauf notes that the Chinese concept of Gu is not analogous or reducible to the Western understanding of acute parasitic infection. In the following passage, Fruehauf (2008) elaborates on the nature of Gu syndrome as a shamanic category of illness, a recalcitrant form of disease, and gives some modern examples:

Not all cases, that, from a classical perspective, would be diagnosed as Gu syndrome, would be patients with parasites, and vice-versa, not all people with a positive parasitic test from the Western perspective would be accurately diagnosed as Gu. Gu syndrome actually means that your system is hollowed out from the inside out by dark yin forces that you cannot see. This not seeing often includes Western medical tests that come back negative for parasites. So from a certain perspective, AIDS falls into this category, with body and mind being hollowed out from the inside out, without knowing what is happening. Gu syndrome originally meant “black magic.” To the patient it felt as though someone had put a hex on them, without anybody—whether it’s the Western medicine community or, in ancient times, the regular Chinese medicine approach—being able to see what was really going on.

Gu syndrome is caused by a dark yin pathogen. As we noted earlier, the idea of a “hidden” pathogen already has psychological resonances. As examples of dark yin pathogens and the pathologies they cause, Fruehauf cites the spirochetal pathogen of Lyme disease along with conditions of chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, dysentery, and viral infections such as herpes. Fruehauf (2008) ultimately differentiates between two subcategories of Gu syndrome—brain Gu and digestive Gu:

Brain Gu is “caused by chronic viruses that target the nervous system (such as coxsackie, herpes, and in some cases HIV), or spirochetes (especially Lyme disease and its coinfections), or other exotic pathogens causing chronic forms of meningitis, malaria, leptospirosis, etc. A lot of patients in this category are diagnosed with fibromyalgia these days. There may be symptoms of body pain, anxiety, depression, headaches, eye aches, visual hallucinations, strange sensations that there is something stuck in their head, etc. Very often these people have been put on Prozac or some other kind of anti-depressant, which often doesn’t work . . . Digestive bloating, pain, and altered bowel movements are the primary signs of Digestive Gu. But both of them will have a certain degree of mental symptoms, therefore the “demonic possession” label—the Digestive Gu less, and the Brain Gu more.

Drawing a parallel between the neurological pathogenesis of brain Gu and demonic possession, Fruehauf classifies possession (with its mental-emotional symptomology) as a nervous system disorder, recalling the ancient observation of epileptic seizures as “possession”.

The treatment of Gu syndrome consists of herbal prescriptions, acupuncture/moxibustion, dietary advice, and qigong exercise. Fruehauf compiles the recommended acupuncture treatment from “Master Ranxi’s Treatise on Expelling Gu” from 1893. The recommendations include several points, including Sun Simiao’s thirteen ghost points:

vigorous garlic moxibustion on BL-43

moxibustion on BL-13, ST-36, and Guikuxie (Demon Wailing Points)

acupressure with menthol preparations on the thirteen ghost points

selective needling of the thirteen ghost points

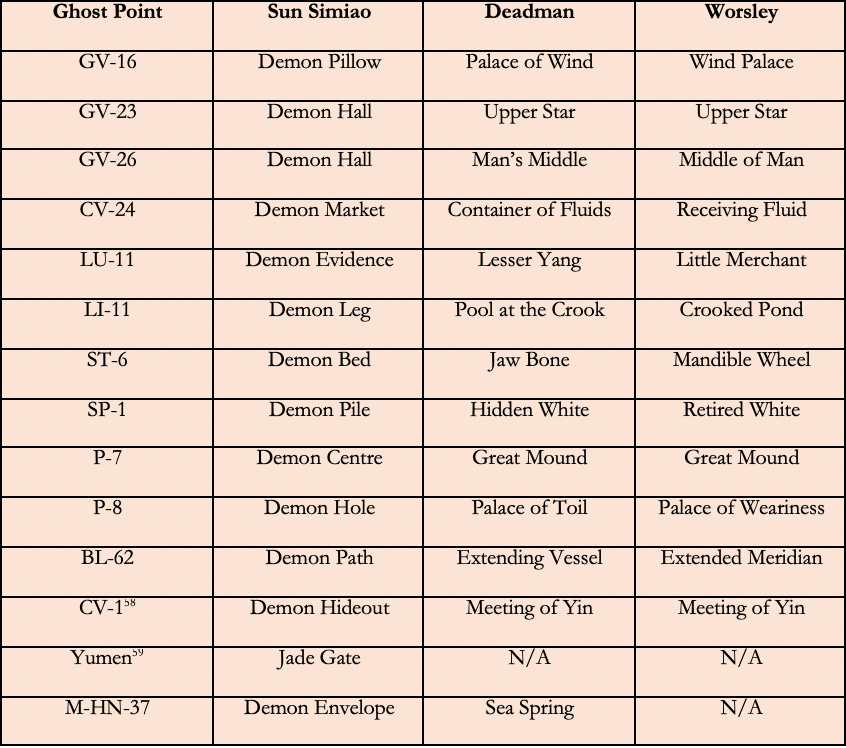

The thirteen ghost points are GV-26 (Demon Palace), GV-16 (Demon Pillow), GV-23 (Demon Hall), CV-24 (Demon Market), LU-11 (Demon Evidence), LI-11 (Demon Leg), ST-6 (Demon Bed), SP-1 (Demon Pile), P-7 (Demon Centre), P-8 (Demon Hole), BL-62 (Demon Path), CV-1 (Demon Hideout) for males / extra point (Yumen) on the head of the clitoris for females, M-HN-20 (Demon Envelope) under the tongue. These points are given “demon” names in the ghost point schema but are given other names in classical sources, as documented by Deadman (2016) and Worsley (2004).[3] (See Appendix B). Unschuld elaborates on the origins of the thirteen ghost points and the roots of acupuncture in shamanism:

In his Ch’ien-chin i-fang, Sun Ssu-Miao cited the physician Pien Ch’io, purportedly active in the fifth century B.C., and indicated the exact location of thirteen puncture points for the needle treatment of demon-related illnesses. The . . . puncture points bear such revealing names as “demon camp,” “demon hearts,” “demon path,” “demon bed,” or also “demon hall”. The needles used to penetrate a “demon heart” in the treatment of an individual were analogous to the spears used by exorcists at the time of Confucius . . . . (Unschuld, 2010, p. 45)

Unschuld comments that it is possible that early uses of acupuncture “originally had purely demonic medicine functions” (Unschuld, 2010, p. 45). The thirteen ghost points are used to treat possession, but we have to examine what possession meant to Sun Simiao. As Jarrett (2005) points out, “definitions of all illness are culturally determined”. (p. 45). In Sun Simiao’s time, possession was associated with symptoms we now understand as mental illness and epilepsy, as Jarrett (2005) remarks, the thirteen ghost points are used “in modern times for the treatment of manic disorders and epilepsy”. (p. 45).

Thus, the demonology of early Chinese medicine has been translated into a psychological paradigm of illness and treatment which Fruehauf asserts is clinically evident and efficacious in pathologies of the gut-brain axis. Modern understandings of the microbiome shed more light on the matter, especially when we consider that neurotransmitters are synthesized and regulated in the gut by intestinal microbiota. Therefore, psychological pathologies manifest in a bi-directional relationship to the gut: microbiome imbalances are reflected in mental-emotional pathologies and psychological disorders are reflected in digestive pathologies. While parasitism can be understood in relationship to the gut-brain axis, it can also be interpreted purely in psychological terms, as Ellenberger (1970) does when he refers to possession as “intrapsychic parasitism” (see Appendix D) and as Worsley does when he links possession with mental and spiritual vulnerability.

II. Acupuncture and Psychoanalysis

In “The Psychologizing of Chinese Healing Practices,” Barnes describes how Western practitioners of Chinese medicine began incorporating psychotherapeutic ideas and explanations into medical theory, where “blocked” emotions and suppressed memories became part of the explanatory model of illness. Barnes (1998) explores how practitioners have cross-pollinated psychotherapy and acupuncture, with some practitioners blending the two and others maintaining strict distinctions:

For [some] practitioners, acupuncture is a plausible alternative to psychotherapy. Indeed, they feel it is possible to perform interventions for psychological problems that would eliminate the need for psychotherapy altogether. Still other practitioners, who distinguish between what one does as an acupuncturist and as a psychotherapist, choose not to blend the two.

The relationship between acupuncture and psychotherapy became a subject of consideration when Chinese medicine entered the European imagination, where acupuncture mingled with psychoanalysis, homeopathy, and naturopathy. The five-element tradition transmitted by J.R. Worsley brought acupuncture into the realm of psychological concern in the 1970s in the UK and America. The American psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Leon Hammer was another significant figure who consciously sought to bridge the two disciplines, regarding Chinese medicine and acupuncture as “congenial therapeutic partners”. (Hammer, 2010).

Worsley and Hammer were influenced by the available literature of the time, including Lawson-Wood’s Five Elements of Acupuncture and Chinese Medicine (1965), regarded by Eckman as the “first coherent book about acupuncture in English” (Eckman, 2007).[4][5] The text presents the basics of Chinese medical theory, emphasizing five-element theory. In a chapter titled “Psychological Considerations,” the authors mention Hahnemann’s Organon and the possibilities of a marriage between acupuncture and homeopathy. They also mention Georg Groddeck, a contemporary of Freud who explored the nature of psychosomatic illness.[6] The authors advocate for acupuncture treatment as an alternative to psychoanalysis:

When we talk about treatment of the psyche we are not thinking in terms of modern Western psychiatry, with use of shock and drugs, but rather in terms of psycho-analysis and systems derived therefrom. (Lawson-Wood, 1965).

Speaking only four years after Jung’s passing, the authors refer to the psychoanalytic tradition as a whole before presenting two key points:

(a) Psycho-analysis, from the patient’s point of view, can be an expensive way of having the psyche treated; especially as a beneficial outcome is by no means certain.

(b) Whether it is in the end successful or not, psychoanalysis seems inevitably to be accompanied by a great deal of emotional torment and distress. (Lawson-Wood, 1965).

With these practical concerns (expense and torment), the authors make a case for the capability of acupuncture to treat the psyche more effectively, more reliably, and with significantly less expense:

It is desirable, therefore, that there should be some alternative and far speedier method of resolving analytical problems. But this does not mean to say that we regard Chinese acupuncture by itself as an alternative to psycho-analysis in all cases; but rather do we intend to convey that a judicious use of Chinese acupuncture points can serve as an extremely useful technique for bringing about more rapid results, without torment, and with greater predictability. (Lawson-Wood, 1965).

We may be inclined to presume that such notions are entirely European in origin. However, the authors continue their thesis by providing classical justifications:

If one wants classical justification for lining psycho-analysis with acupuncture, we draw attention to the passages in the Nei Ching dealing with interpretation of dreams. Several thousand years before Freud the Chinese recognized that dreams represent a mechanism for symbolic wish-fulfillment.[7]

There should be no difficulty in appreciating that any disturbances in the flow and balance of Life-Force, with its two poles YANG and YIN, manifests itself as a disturbance of some degree in both psyche and soma. (Lawson-Wood, 1965).

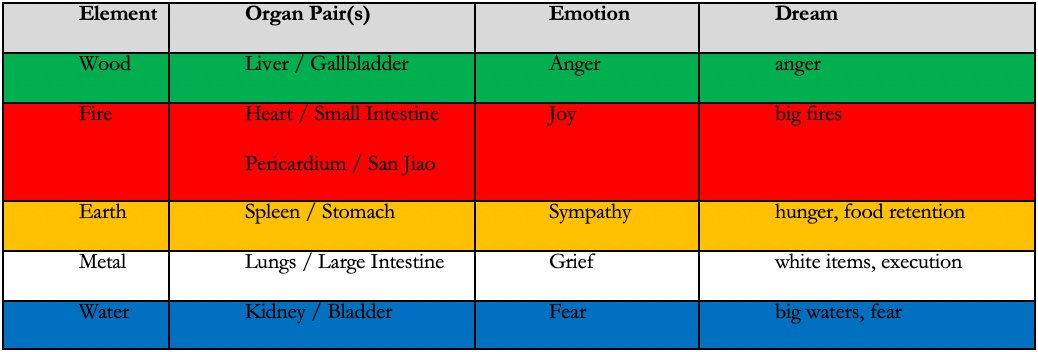

The authors are referring to several passages from the Nei Jing that discuss pathological dreams. The first mention of dreams is found in chapter seventeen, “Discourse of Vessels and the Subtleties of the Essence,” verses 102-3:

When the yin [qi] abounds,

then one dreams of wading through a big water and is in fear.When the yang [qi] abounds,

then one dreams of big fires burning.When both yin and yang [qi] abound,

then one dreams of mutual killings

and harmings.When [the qi] abounds above,

then one dreams of flying.When [the qi] abounds below,

then one dreams of falling.When one has eaten to extreme repletion,

then one dreams of giving.When one is extremely hungry,

then one dreams of taking.When the liver qi abounds,

then one dreams of anger.When the lung qi abounds,

then one dreams of weeping.When there are many short worms,

then one dreams of crowds assembling.[8]

The passage mentions several types of dreams. The dreams associated with organs reflect elemental and emotional correspondences in the five-element schema. Thus, “when the liver qi abounds, then one dreams of anger”. In the case of the Lung, the corresponding sound (weeping) is given instead of the emotion (grief), “when the lung qi abounds, then one dreams of weeping”. The Kidney is not mentioned by name but is associated with “yin qi” and “dreams of wading through a big water . . . “and fear.” The Heart is also not mentioned by name but subsumed in the category of “yang qi” that “abounds,” causing dreams of “big fires burning.”

“Dreams of crowds assembling” as a result of “many short worms” is a reference to parasitic infection. Dreams “of taking” when “one is extremely hungry” is the classic example of a wish-fulfilling dream. Some dreams simply reflect the pathological condition itself: “when the qi abounds above, then one dreams of flying”, “when the qi abounds below, then one dreams of falling”. Another type of dream reflects the opposite nature of the pathology: “When one has eaten to extreme repletion, then one dreams of giving,” a reference to food retention and the Earth element.

In chapter eighty, “Discourse on Comparing Abundance and Weakness,” dreams are mentioned again. Verse 568-5 states:

It is therefore that

a recession of [the type] being short of qi

lets one have absurd dreams.In extreme cases, this leads to hallucinations.

(Unschuld, 2016).

Being “short of qi” is defined as qi stagnation in the yang meridians and qi deficiency in the yin meridians. In the following verse, five-element correspondences are referenced again in a dream associated with the Lung:

Therefore,

when the lung qi is depleted,

then this causes man in his dreams to see white items,

to see people executed, with [their] blood flowing in all directions.When it is its time,

then he dreams of weapons and combat.

(Unschuld, 2016).

In this verse, the corresponding color of the Metal element is represented as the “white items” in the dream. We need only reflect on the potentially sharp and destructive quality of the Metal element to see the significance of the “vision of execution.”[9] “When it is its time” refers to the three months of Autumn in which the Metal element predominates. The chapter discusses dreams resulting from the depletion of liver qi, kidney qi, heart qi, and spleen qi. A concluding verse states:

In all these [cases],

the qi of [one of] the five depots is depleted.The yang qi has a surplus, while

the yin qi is insufficient.

(Unschuld, 2016).

In other words, these dreams arise when the yin organs become deficient, resulting in overall yin deficiency and yang excess. This is why “dream-disturbed sleep” is generally regarded as a symptom of yin deficiency and/or pathogenic fire. Daoists view the having of dreams as an inherently pathological state, and the ceasing of dreams is symbolic of having transcended the psyche and thus become “immortal”—as Hammer recounts, “some authorities on Chinese medicine believe that a contented spirit does not dream.” (Hammer, 2005).

The dreams referenced in the Nei Jing illustrate a psychosomatic paradigm, with dreams functioning as a link between them. We can only retrospectively consider this to be “psychological” since the systematized discipline we call “psychology” is a nineteenth-century phenomenon, but its subject—the psyche—is universal. The psyche itself precedes nomenclature and tradition. Therefore, the so-called “psychologizing” of Chinese medicine may be a twentieth-century phenomenon of an indigenous medicine in exile, but this is only true in the superficial context of semantics. With its understanding of the pathogenesis of dreams, emotions, and organic imbalances, Chinese medical theory contains a psychotherapeutic paradigm.

Worsley gives diagnostic value to dreams, but cautions against overemphasizing their importance. He writes that a “dream can signify a message from a particular official” and that “such a dream, oft-repeated, may point specifically towards the element in distress which is causing element-related images to disturb the unconscious mind”. (Worsley, 2012, p. 110)

Possession, Superego, and Western Psychiatric Disorders

Ellenberger (1970) distinguishes between two types of possession: somnambulic and lucid. He notes that in Catholic theology, “possession” refers to the “somnambulic” form, while “obsession” refers to the lucid form, a word he notes “has been adopted by psychiatry”. (Ellenberger, 1970). Worsley thus indicates a psychiatric pathology when he links spiritual deficiency with becoming “possessed by obsessions.” The theme of “obsession” gives us an immediate link to obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). OCD was initially known as “scrupulosity,” a reference to the term “scruples” in religious literature, meaning “obsessive concern with one’s own sins and compulsive performance of religious devotion.” The etymology of “scruples” traces to the Latin scupulum, meaning a “sharp stone” and implying a “stabbing pain on the conscience.” The eighteenth-century French psychiatrist Jean Esquirol described OCD as “monomania” and “partial insanity.” In the early nineteenth century, the French psychiatrist Henri Dagonet described OCD as “the more one tries to discard an idea, the more it becomes imposed upon the mind, the more on tries to get rid of an emotion or tendency, the more energetic it becomes.” In other words, repression is obsession is possession. Dagonet’s description thus conjures the Freudian concept of repression, that what one denies becomes repressed in the unconscious, where it gains strength through compensatory neuroses and defense mechanisms.[10]

In the late nineteenth century, Freud characterized obsessive-compulsive illness as an “obsessive neurosis” (zwangsneurose) arising from a deep inner conflict in the unconscious mind. His phrase is the origin of the modern terminology of “obsessive-compulsive disorder.” Freud viewed obsessive neurosis as a maladaptive pathology fueled by an egoic conflict between the id and superego. As Freud described, the superego is an “ego ideal,” the realm of the conscience, an internalization of parental and societal images, and the repressive force of conditioning.[11] The conflict between the ego and the “ideal” (superego) “reflect the contrast between what is real and what is psychical, between the external world and the internal world.” (Freud, 1960). This confusion between internal and external reality may be a hallmark of possession: the patient cannot access his own mental and spiritual resources (ego) and, in extreme cases, does not know how to function in society (superego). As a result, the patient’s libido (id, psychic energy)[12] remains deeply repressed.

Jung described the superego as an internal moral voice that arises from the anima/animus. He argued that this aspect of the psyche is both “consciously acquired” and “an equally conscious possession”:

The Freudian superego is not, however, a natural and inherited part of the psyche’s structure; it is rather the consciously acquired stock of traditional customs, the ‘moral code’ as incorporated, for instance, in the Ten Commandments. The superego is a patriarchal legacy which, as such, is a conscious acquisition and an equally conscious possession. (Jung, 1970).[13]

We have to note yet another shadow quality of the superego: perfectionism. The perfectionistic drive so often accompanies obsessions that they are practically inextricable. Perfectionism arises from the superego’s internalization of parental and cultural values and the conscience-driven need to fulfill them perfectly. Freud notes that the superego pursues perfection over and against the pleasure and reality principles (which belong to the id and ego, respectively). However, we have to apply this knowledge carefully: not every patient with perfectionistic tendencies is possessed, and not all perfectionistic drives are pathological.

Freud and Jung concluded that obsessive neuroses are a pathology in the unconscious egoic structure caused by a range of repressive reactions to moral, ethical, childish, emotional-sexual, and.or cultural conflicts. Thus, it can be argued that possession (as an obsessive pathology) is necessarily possession by the unconscious superego.

OCD is now woven into the modern colloquial lexicon, where “being OCD” is casually mentioned as a behavioral synonym for “anality.” Of course, the anality of OCD can only serve to bring us back to Freud, who traced many adult neuroses to arrested psychosexual development in the “oral,” “anal,” and “genital” stages of early life.[14] The anal stage spans from ages one to three and concerns the erogenous zone of bowel and bladder elimination. Psychological fixation in the anal stage results in “anal retentive” and “anal expulsive” pathologies. In five-element theory, eliminative pathologies belong to the Metal and Water elements. Whether patients diagnosed with possession also exhibit eliminative symptoms (constipation, diarrhea, nocturia, dysuria, enuresis, etc.) is worthy of further clinical exploration.[15]

From the perspective of psychoanalytic psychology, the treatment of OCD is the classic “talking cure,” whether in the form of Freud’s original “psychoanalysis” or Jung’s “analytical psychology.” Today, cognitive-behavioral models of psychology have become dominant, with treatments consisting of cognitive behavioral therapy and SSRI medications: fluoxetine (Prozac) for seven years and older, fluvoxamine (Luvox) for eight years and older, paroxetine (Paxil) for adults only, sertraline (Zoloft) for six years and older, and clomipramine (Anafril) for ten years and older. (Mayo Clinic, 2023). Other treatments include outpatient and residential treatment programs, deep brain stimulation,[16] and transcranial magnetic stimulation.[17]

Spirit and Psyche

We must remember that a psychic substance does not and cannot mean one thing

—James Hillman, Alchemical Psychology, 2009.

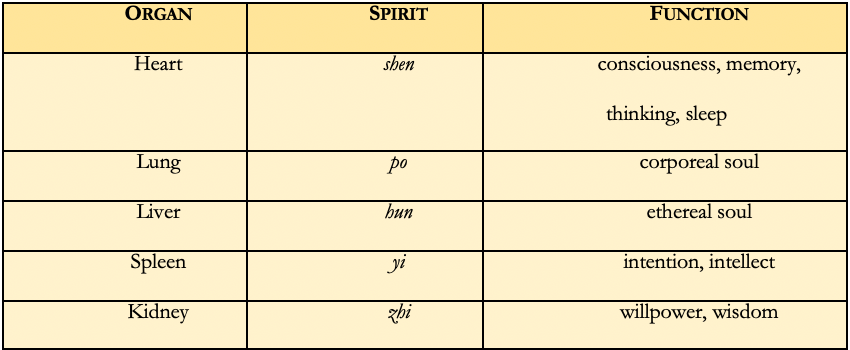

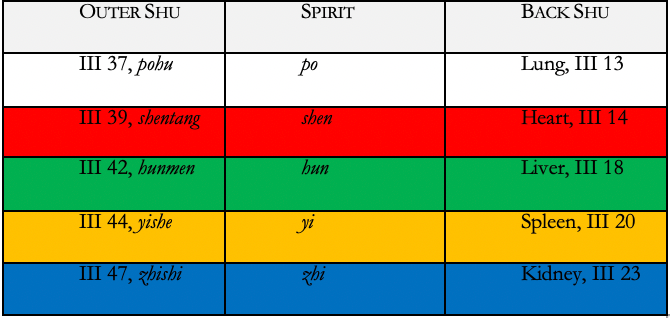

What the Chinese call shen, the Greeks call psyche. While the term “spirit” has been adopted as a standard English translation for shen, the Chinese concept includes “spirit” and “soul.” The three treasures are expanded into five shen that reside in each of the yin organs:

The Heart is the seat of shen—consciousness, memory, thinking, and sleep.

The Lungs are the seat of po—the corporeal soul that animates the body while alive.

The Liver is the seat of hun—the ethereal soul that wanders outside of the body and survives death.

The Spleen is the seat of yi—intentionality and intellect.

The Kidneys are the seat of zhi—willpower and wisdom.

The five shen describe the psychological qualities of the organs, illustrating the Chinese vision of organic physiology as a network of communication that integrates the body, mind, and spirit. The five shen are the spirits that naturally possess us.[18] They are the most profound aspect of organ function, the spirit of the physiology, the ghost in the machine.

Anima and Animus

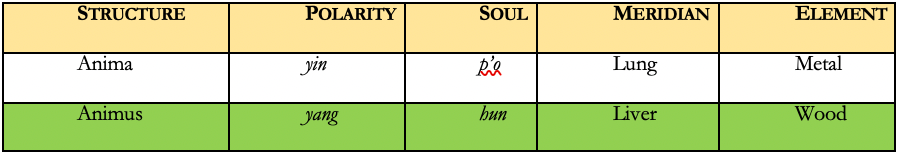

Jung correlates the anima and animus with the hun and p’o, respectively. He writes:

According to our text, among the figures of the unconscious there are not only gods but also the animus and anima. The word hun is translated by Wilhelm as animus. Indeed, the concept ‘animus’ seems appropriate for hun, the character for which is made up of the character for ‘clouds’ and that for ‘demon’. Thus hun means ‘cloud-demon’, a higher ‘breath-soul’ belonging to the yang principle and therefore masculine. After death, hun rises upward and becomes shen, the ‘expanding and self-revealing’ spirit or god. ‘Anima’ called p’o, and written with the characters for ‘white’ and for ‘demon’, that is, ‘white ghost’, belongs to the lower, earth-bound, bodily soul, the yin principle, and is therefore feminine. After death, it sinks downward and becomes kuei (demon), often explained as the ‘one who returns’ (i.e. to earth), a revenant, a ghost.[19]

Jung’s articulation of the anima/animus extends from his notion of the unconscious as a structure of polarities. Every man has a feminine shadow known as the anima, and every woman has a masculine shadow known as the animus. The failure to integrate with these polarized unconscious elements is the source of all neurosis. Jung is drawing on Latin as he often does, where anima means “mind, soul” and animus means “spirit, mind.” Anima is yin, animus is yang; anima is the p’o soul, animus is the hun soul.

Jung discussed anima- and animus-possession as pathological states in which the unconscious shadow engulfs the psyche. One is possessed by the anima or animus, by the p’o or the hun. In this sense, we can interpret the broad category of yin or yang syndromes in terms of anima/animus possession: anima possession is a yin complex, animus possession is a yang complex. Severe possession by the anima or animus may result in the form of possession discussed by Worsley. However, anima/animus possession may also be evident as a Husband-Wife imbalance, Liver-Lung block, or a split within an element.

The Husband-Wife imbalance is a severe block that Worsley considered life-threatening. The basic premise of the block is that the right-hand pulses are stronger in quantity and quality than the left-hand pulses. This pulse picture is interpreted by Worsley as a separation of yin and yang, which is how Chinese medicine describes death. Given the feminine/masculine polarities of the anima/animus, we can surmise a severe conflict between these aspects as a relational crisis (either internal or external).

The Liver-Lung is one of several possible “exit-entry” blocks. This particular block is diagnosed when the Liver pulse (left middle position, deep) is excess relative to the Lung pulse (right first position, deep). Since the Lung follows the Liver in the circulatory flow of the meridian clock, this pulse picture is interpreted as a failure to transfer energy from the Liver to the Lung in the natural circulation cycle (per the meridian clock).[20] We can interpret the Liver-Lung block as a form of animus possession—the deficient Lung pulse shows that the p’o (or anima) is repressed and dominated by the animus (or hun). This would lead us to theorize that the Liver-Lung block is more common in women, but this premise needs further clinical evaluation.

The failure of the integration between the anima/animus can also manifest as a “split within an element”. This split within an element refers to an unequal amount of energy in the paired organs of a single element. When this block is evident, the superficial and deep pulses of the same position will differ in quantity. For example, if the Liver pulse is noticeably deficient in relationship to the Gallbladder pulse, then the paired organs of the Wood element are not sharing energy equally. Since the paired organs of an element are necessarily a yin-yang polarity, the split within an element indicates a defense mechanism destabilizing an element’s polarity. Jung’s definition of neurosis as “one-sidedness” comes to mind, as does Freud’s consideration of “splitting” as a defense mechanism. In the example of deficient Liver / excess Gallbladder, the anima represses the anima. (The association between anima-animus and yin-yang can be made for the remaining organ pairs within each element).

Possession as Complex

A psychoanalytical view of spirits views their existence and perception as a projection from the unconscious. Spirit phenomena are interpreted as a psychological phenomenon, rather than an ontological reality. Thus, possession is re-interpreted as a complex rather than an entity.

In “The Psychological Foundations of Belief in Spirits,” Jung (1969) argues that belief in spirits is itself the result of mental illnesses such as hysteria, schizophrenia, and nervous disorders. In anthropological fashion, he argues that what possesses us is the notion of possession itself. However, Jung’s intention is not to discount the phenomenon of spirit-possession; rather, it is to enfold possession within a psychological phenomenology. Thus, Jung asserts that the belief in and experience of possession results from an animistic consciousness, a participation mystique[21] in which the dream world and physical reality are fluidly merged. Jung (1969) identifies three phenomena in particular as the origin of belief in spirits: (1) “the seeing of apparitions, (2) dreams, (3) pathological disturbances of psychic life”. He describes these three phenomena as “psychic fragments” and places them in the “autonomous complexes” category.

In Jungian psychology, a complex represents an unconscious and thus disconnected aspect of the psyche: “Although the separate parts are connected with one another, they are relatively independent.” (Jung, 1969). What is separated from the whole becomes pathological, and its incomplete view of reality possesses our psyche. Therefore, all that we fail to integrate with becomes a complex of psychic possession.

Through our experiences in dreams, apparitions, and visions, we associate with an aspect of the psyche independent of the waking-state ego. Where do dreams, apparitions, and visions come from? Jung describes all three as an “irruption from the unconscious” in different contexts: dream is a “psychic product originating in the sleeping state without conscious motivation”; visions are “like dreams, only they occur in the waking state”; and apparitions are hallucinations from mental illness where “quite out of the blue . . . the ear, excited from within, hears psychic contents that have nothing to do with the immediate concerns of the conscious mind”. (Jung, 1969).

If dreams, apparitions, and visions are all irruptions from the unconscious, then belief in spirit-possession—and, by extension, the phenomenon of possession itself—is caused by a repression of unconscious material. Jung distinguishes between spirit-possession and soul-loss, correlating spirit-possession with the collective unconscious and soul-loss to the personal unconscious. Indeed, we see this idea in Worsley’s interpretation of possession as a psychic “block,” not as possession by a demonic entity but as possession by the shadow.

III. Possession in Five-Element Acupuncture

In the twentieth century, possession was re-examined by European thinkers. Freud, Jung, Ellenberger, and Worsley each brought forth a new cultural interpretation of spirit-possession as a psychological phenomenon rooted in the unconscious. In particular, Worsley’s presentation of possession represents a critical intersection between nineteenth-century psychoanalysis and classical acupuncture. (See Appendix C). As we encounter Worsley’s concept of possession, we will see how he articulates a theory of possession that leaves behind its demonological past and places it more firmly in a psychological category of illness.

Possession and the Somatic Unconscious

The part of the unconscious which is designated as the subtle body becomes more and more identical with the functioning of the body, and therefore it grows darker and darker and ends in the utter darkness of matter. . . . Somewhere our unconscious becomes material, because the body is the living unit, and our conscious and our unconscious are embedded in it: they contact the body. Somewhere there is a place where the two ends meet and become interlocked. And that is the [subtle body] where one cannot say whether it is matter, or what one calls “psyche.”

—C.G. Jung, Nietzsche’s Zarathustra, 1939.

If possession is a psychological pathology, then its treatment by acupuncture implies the existence of a somatic unconscious. The unconscious offers the meaning-values of interior, hidden, and yin. Therefore, the unconscious is the yin aspect of the psyche, the shadow of the spirit.

The unconscious can be posited as an interior and hidden structure analogous to the meridian system. The meridians function as invisible pathways that link the body's organs, emotions, and spirits, serving as unconscious structures within human physiology. The psyche is thus understood not only as the mind but as a substance in circulation. Meridians are thus the pathways of psychic circulation, a structure of the unconscious, the invisible domain of archetypes, images, and ancestries residing in our bodies. Meridians are interior, invisible, and hidden, but they are also palpable structures capable of being assessed and treated. We once drove demons out of bodies with spears, and now we adjust the psyche with the intention of fine needles.

The vessels of acupuncture are not reducible to arteries, veins, nerves, or pathways of fascial conduction. The vessels of acupuncture are invisible lines that circulate the vital essence known as qi. This is the image of an alchemical vessel—a container, cauldron, rotundum. A vessel is a method of containment. As a jug carries water, the vessels carry the life-force throughout the body, providing a container for qi. We heat the vessels with fire and puncture the vessels with metal to engender an alchemical transformation that is at once physical, mental, and spiritual. Thus, the alchemical vessels of the body are shapes of soul—pathways within which the spirits of libido circulate, containers within which the unconscious is made conscious.

Jung found that his psychological discoveries were best represented in the language of alchemy. In his commentary on The Secret of the Golden Flower, Jung (1962) remarks that “in content it is a living parallel to the psychic development of my patients.” (pp. 86-87). Jung discusses the nature of circulation as a symbol of psychic development, drawing parallels to the image of mandalas. Jung (1962) writes, “This symbolism refers to a sort of alchemical process of refining and ennobling; darkness gives birth to light; out of the ‘lead of the water-region’ grows the noble gold; what is unconscious becomes conscious in the form of a process of life and growth.” (p. 102). Circular movement is the nature of qi—and qi moves in vessels. The meridian structure thus becomes a circumambulatio of psychic circulation. Therefore, it is not so far-fetched to imagine that by puncturing the meridians, we are restoring psychic circulation where it has become stagnant, perverse, rebellious, invasive, or blocked.

Definition and Etiology

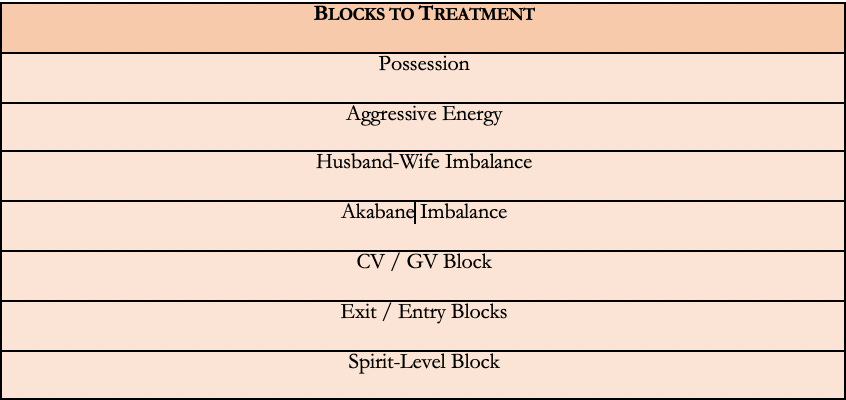

Worsley placed possession within the clinical schema of “blocks to treatment”, which he defines as secondary imbalances that prevent treatment efficacy and which therefore must be addressed before the root-treatment of the “causative factor” (C.F.).[22] Worsley describes seven different blocks to treatment. One or more may be present in any given treatment. (See Appendix C.)

If we accept the psyche as a circulatory process, then blocks represent an inhibition, even repression, of this natural flow. If health is circulation, then disease is a block. Stated differently—if health is sufficiency, then disease is insufficiency (or deficiency).

In Worsley’s system, possession is regarded as one of the more severe blocks to treatment. The idea of a possessed patient returns us to the magical context of shamanism and “spiritual” cure, but Worsley’s presentation of possession is less magical and more psychoanalytical. At the outset, Worsley (2012) disavows the demonic and other-worldly connotations of possession, defining it instead as a loss of psychological agency:

To many people, including students of acupuncture, the terms 'possession' and 'being possessed' may sound rather melodramatic and archaic. They are usually associated, in the psychological sense, with stories from the Bible and those modern horror films depicting the way people used to explain madness years ago. However, we only need to consider 'possession' in the basic and simple sense of 'taking over' to appreciate how appropriate it can be as the description of what we may find happening to some patients. It is as if some external agency or force has taken over a part of that person's control of energy. In a very real way, that person is no longer in control of his whole self. Someone who has lost control of a part of his energy system is not going to be able to respond properly to treatment. (p. 170)

Here, Worsley references the literal meaning of “possession” as “taking over”. Possession comes from the Latin possess-, meaning “occupied, held”. In Worsley’s interpretation, possession is a loss of autonomy and subsequent loss of access to vital resources. In other words, a possessed patient has lost connection to themselves—there is a vacancy in their spirit. A psychoanalytic interpretation indicates that the patient is not possessed by an external spirit or demon, but by the shadow of the unconscious.

Worsley (2012) places the etiology of possession internally, where a weakness of “spirit” leaves the person vulnerable to negative influences from within and without:

. . . A person who is strong in spirit, no matter how weak or defective his body, will not be as affected by internal or external destructive forces as someone whose spirit is weak. People whose mental and spiritual resources are deficient are vulnerable. They can more easily become possessed by obsessions of one kind or another. Sadly, this vulnerability is becoming more rather than less common and its incidence owes a great deal to the priorities which our present society sets for itself. (p. 170)

Mental and spiritual weakness leads to vulnerability, and vulnerability leads to obsessions—these are the keywords we will see repeated in five-element discussions of possession.[23] Worsley (2012) elaborates on the nature of obsessive behavior, giving the example of anal-retentive compulsions:

There are the sad cases of people who have become so worried about dirt and obsessed with hygiene that all through the day they have to wash themselves over and over . . . There are other people who become obsessed with the idea that they are failing to do something perfectly. They will continue to repeat the same sequence of actions over and over again because they are never satisfied. If we come across anything in the patient’s behaviour or case history that suggests obsessions of any kind, we become alerted to the possibility of possession. (p. 173)

Worsley’s description of obsessive behavior is similar to the Western psychiatric diagnosis of OCD and related disorders. Western psychiatry has explored the relationship between obsessive neuroses and possession since the early nineteenth century. More importantly, obsession implies a loss of control, and loss of control is Worsley’s fundamental definition of possession.

Worsley refers to mental and spiritual weakness as a cause of possession. What does he mean by this? Worsley’s usage of “spirit” is an approximation of the Chinese shen, a term which is closer in meaning to the Greek “psyche” than it is to the common understanding of something “spiritual.” From a psychological perspective, a depletion of mental and spiritual resources describes a psychic deficiency, a loss of access to the psyche, a vacancy in the soul. Loss of access is another way of saying “unconsciousness”. When we lose access to the psyche, its resources and truths become invisible to us. Engulfed in the shadow of the unconscious, we become vulnerable to impositions of all kinds.

Worsley discusses the etiology of possession in broad terms, as there is no singular cause of the condition. In classical fashion, he organizes the etiology into internal and external causes:

Causes of possession can be internal or external, and they are not necessarily confined to mental and spiritual levels only. A physical shock, such as exposure to a sudden and extreme change of climate or temperate, can lock a person’s energy system into an abnormal pattern which he cannot unlock and restore to normal. At the mental level, possession can be caused by an external influence, as in the case of people who succumb to the hypnotic power exercised over them by others . . . In the majority of possession cases, however, the causes are internal. Such possession can take place either suddenly or insidiously over a period. The former can happen as the result of some terrible and shocking experience which literally terrifies the person out of his mind. The latter can happen, for example, in the case of drug-taking where the person is taken over by so-called ‘mind-expanding’ drugs; or in the case of meditation techniques intended to induce ‘out of body’ experiences. (Worsley, 2012, p. 173)

Worsley lists climatic shocks, psychological shocks, mind control, psychedelic drugs, and out-of-body experiences as potential causes of possession. Shock unseats the spirit, making us vulnerable to possession. Worsley’s mention of psychedelic drug use and meditation-induced experiences is primarily a criticism of escapism and disembodiment via a stimulus of some kind (whether drugs or meditation). However, these critiques cannot be taken as blanket statements. Worsley is pointing out possibilities, and we should not jump to conclusions simply because a patient discloses drug use or meditation practice. What makes health and disease in each person is unique to that person, their motivations, and the larger context of their life.

Worsley also suggests that possession has a cultural etiology, noting that spiritual vulnerability is becoming more common due to the “priorities which our present society sets for itself”. The idea that cultural conditioning is a cause of illness was one of Freud’s most influential observations.[24] Echoing his view, Hillman writes:

Our neurosis and our culture are inseparable . . . [it was] Confucius who insisted that the therapy of culture begins with the rectification of language. Alchemy offers this rectification. (Hillman, 2009)

Referencing Confucius and alchemy, Hillman brings the consideration of culture and illness into the history of Chinese medicine. The “rectification” of culture or patient also leads us to the Chinese medical concept of zheng qi—the “upright” or “righteous” qi.

The concept of zheng qi describes the body’s ability to maintain health in the face of external pathogenic factors. While it has some resonances with the Western medical concept of “immunity”, zheng qi is more than physical immunity—it is the integrity of the body, mind, and spirit that keeps us vulnerable and susceptible to possessions of all kinds. We can thus trace Worsley’s observations of “vulnerability” and “susceptibility” to a deficiency of zheng qi. The function of zheng qi can be further elaborated as a conflict between zheng qi and xie qi where xie qi is translated as “perverse”, “evil”, or “pathogenic” qi. The upright qi prevents susceptibility to and eliminates pathogenic (or xie) qi. Thus, a deficiency in zheng qi results in an accumulation of xie qi. The relationship between zheng qi and xie qi may also help us understand why Worsley advised draining aggressive energy after clearing possession.[25]

Returning to Worsley’s assertion of a cultural etiology in possession, we understand xie qi to include any external pathogenic factor—including community, culture, society, and civilization. This focus reflects the Confucian understanding of the import of society and the “rectification” of virtues that enable harmony between the individual and society. Rectifications include the cultivation of five virtues—ren (compassion), yi (selflessness), li (recognition of the sacred), zhi (wisdom), and xin (integrity).[26][27]

Diagnosis and Pathogenesis

According to Worsley, possession can only be diagnosed by looking into the patient’s eyes. The practitioner knows the patient is “possessed” when there is a vacancy in the eyes, described by Worsley as the feeling that no one is looking back at you. This is distinguished from a sense of dullness or resignation in the eyes, signs that constitute a “spirit-level block” and lead to a different treatment protocol (which we will discuss shortly). Possession is diagnosed via the eyes because Chinese medicine regards the eyes as the “seat of shen”, confirming the adage that the eyes are the “windows to the soul”. Hammer elaborates on the Chinese concept of shen and its relationship to the Heart, Liver, and eyes:

The combined shen qi is the ‘spirit’ of the individual, which is said to live in the Heart by day, and in the Liver by night. During the day it may be accessed through the pupils of the eyes. In health it will be expressed as a shining light. In disease it may be dull, withdrawn, or out of control (wild). At night, it rests in the Liver and may be assessed by a person’s dreams. (Hammer, 2010, p. 6)

If we look at possession in terms of shen, then it appears to be more than a shen deficiency—it is an obscuration of shen, an eclipsing of the Sun within. According to Worsley, a possessed patient is fundamentally “unreachable.” Worsley (2012) continues to describe the possessed patient as someone drowning in the mask of persona:

How do we recognise that somebody is possessed? If his energy state is partially or seriously beyond his own control, we will soon sense that we are failing to reach him, that we are not really communicating with him. We will find that we are not getting honest responses, that we are continually talking to a mask or shell. (p. 170)

“Persona” literally means “mask”. Jung describes the persona as a compensatory personality that represses the unconscious. Persona is the “social face,” the constructed presentation in diametric opposition to the “Self.”[28] Therefore, the possessed patient may have a powerful persona, a mask that the practitioner needs to see behind for a proper diagnosis. While everyone exhibits a persona to one degree or another, those who are lost in their persona become vulnerable to possession. Thus, a practitioner may encounter various types of personalities with diverse levels of coherence. A possessed patient is not necessarily a psychiatric case, but Worsley (2012) gives possession psychiatric connotations when he describes the “worst cases”:

The worst cases are those where the person has lost control of mind and spirit to such an extent that he ought to be in a mental home under external care and control. In such cases, where the person is totally possessed, he simply cannot be reached, nor can he make any sense of what is happening around him. (p. 170)

Worsley indicates that the most severe forms of possession are akin to psychosis or “total insanity” (Worsley, 2012). He acknowledged that acupuncturists are not likely to see “many extreme cases of possession”. We can correlate such cases with “psychotic disorders”, a category in the DSM-5 that includes schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder, brief psychotic disorder, psychotic disorder due to a general medical condition, substance-induced psychotic disorder, and unspecified psychotic disorders. Key symptoms across this class of disorders include delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, and manic or major depressive episodes.[29] (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2016)

Traditional accounts of demonic possession have been translated into the clinical language of psychiatry as “schizophrenia”, due to the overlapping nature of the symptoms (hallucinations, hearing voices, etc.). Irmak (2012) holds that demonic possession may be a viable explanation for the hallucinations of schizophrenia:

We thought that many so-called hallucinations in schizophrenia are really illusions related to a real environmental stimulus. One approach to this hallucination problem is to consider the possibility of a demonic world. Demons are unseen creatures that are believed to exist in all major religions and have the power to possess humans and control their body. Demonic possession can manifest with a range of bizarre behaviors which could be interpreted as a number of different psychotic disorders with delusions and hallucinations. The hallucination in schizophrenia may therefore be an illusion—a false interpretation of a real sensory image formed by demons.

Irmak (2012) notes that the treatment of schizophrenia by a local faith healer has proved successful, with patients becoming “symptom-free after 3 months”. Irmak concludes that medical professionals should work in tandem with traditional healers to improve treatment outcomes for schizophrenia. While five-element acupuncture is not a form of “faith healing”, it does accommodate and operate within indigenous views of the world and illness. Therefore, I expand upon Irmak’s suggestion and propose that medical professionals consider the role of five-element acupuncture in treating possession syndromes.

In terms of diagnosis, Worsley cautions against developing any conceptual protocol around diagnosing possession and differentiates it from personality limitations of introversion or stylistic limitations in communication. Worsley (2012) calls practitioners to see with the eye of spirit to diagnose possession:

If diagnosis of possession were simply a matter of recognizing a particular look in the eye or a particular kind of introverted behaviour, then we would simply be able to look it up in a textbook and diagnose it in five minutes. Possession, however, is far too subtle for that. It is not simply a temporary failure to communicate. It is a failing of the spirit of the person, and in order to see it clearly, we have to be able to see with our own spirit. (p. 171)

While we can notice many similarities between the symptomology of possession and Western psychiatric disorders, the two do not necessarily overlap. A patient with a Western medical diagnosis of OCD or schizophrenia may not necessarily be possessed per Worsley’s criteria. It is best if we view these conditions as possibly overlapping but not directly correlative. For one, the diagnosis of possession relies on a subtler form of perception than symptomatic analysis. Therefore, in the context of acupuncture, possession remains a spirit-level pathology diagnosed by the practitioner’s spiritual eye.[30]

Treatment: Seven Devils, Seven Dragons

The quality of an acupuncture point is metaphorically embedded in its name—this principle can be applied to all of the point names and the functions they represent.[31]

—Sun Simiao

Worsley taught two acupuncture protocols for clearing possession: “internal and external dragons.” While the protocol is clearly described in the mythical language of the Chinese imagination, it is not referenced in any texts. Worsley attributes the protocol to the oral tradition of his teachers.

Worsley (2012) describes possession as “being taken over by” seven devils. In the broader context of Chinese medicine, the seven “devils” refer to the seven emotions (qi qing): joy, anger, worry, grief, fear, fright, and pensiveness. By needling a sequence of seven points with a specific needle technique, the practitioner could release the “seven dragons” to consume these seven devils:

The ancient Chinese used picturesque language to describe possession and its removal. They spoke of people being taken over by external or internal devils, and needling the special points as releasing the seven external or internal dragons which could drive the devils away. (Worsley, 2012, p. 174)

On the nature of the protocol, Worsley (2012) indicates that possession treatment is not technically part of the five-element tradition but is utilized as a preliminary procedure:

Such treatment follows set formulae and hence belongs to what we call a different ‘patron’ of acupuncture . . . However, Worsley Acupuncture will not work if possession is present, we must ‘borrow’ this method of removing it. (p. 173)

The seven-needle protocol for “releasing the seven internal dragons” is mostly located on the Stomach meridian: CV-15, master point[32] (Dove Tail), ST-25 (Heavenly Pivot), ST-32 (Prostrate Hare), ST-41 (Released Stream). When needled bi-laterally, a total number of seven needles are employed. The points are needled top to bottom with what Worsley calls “sedation technique”—right to left and retained with a 180°counter-clockwise action on the needle.[33] A perpendicular insertion to the appropriate fen[34] depth is favored for all points. The needles are retained for up to twenty minutes. The practitioner only knows that possession has cleared by looking into the patient’s eyes again.[35] If, after twenty minutes, there is no change in the patient’s eyes, then the practitioner should tonify the needles (left to right, 180° clockwise action).[36] Once the needles are removed, the hole should be left open, to “vent”.

A variant protocol first published in Worsley’s Acupuncturists’ Therapeutic Pocket Book (1975) substitutes a “master point below ST-36” for ST-32 in cases of “possession with depression”.[37] This protocol was subsequently maintained in the first, second, and third editions of Worsley’s Meridian and Points textbook.[38] According to Judy Worsley, when the fourth edition was being revised in 2003, J.R. Worsley suggested its removal:

When we were revising the fourth edition of Meridians and Points, J.R. felt that it would be best to remove the possession with depression protocol. J.R. remarked that it was not something he really found useful in practice and that it added unnecessary complication to the possession treatment protocol. He said that in his experience, the internal dragons protocol without depression works in all cases of possession. The other thing that was concerning to him was that whether or not someone has depression is too subjective of a factor. If you say to somebody, “Do you feel depressed?” it becomes too focused on a symptomatic orientation. Ultimately, J.R. felt that the possession with depression protocol introduces a level of complication that is not needed or clinically useful. (Judy Worsley, personal communication, June 19, 2024)

If possession has not successfully cleared with the internal seven dragons protocol, then the practitioner should re-check their point location before moving on to the seven external dragons protocol. The external dragons are invoked with the same technique but with the patient seated upright:[39] GV-20 (One Hundred Meetings), BL-11 (Great Shuttle), BL-23 (Kidneys Correspondence), BL-61 (Servant’s Aide).[40]

The seven internal dragons correspond to pathological emotions; the seven external dragons correspond with climatic factors: cold, wind, heat, fire, dampness, dryness, and trauma. Despite this theoretical link, Worsley does not consider emotional symptoms or climatic invasions as a basis for diagnosing possession, owing to his emphasis on direct perception rather than symptomatic analysis. As with several of Worsley’s treatment protocols, clearing possession is a potentially multi-step protocol. It should be noted that internal and external dragons are not chosen based on the perceived nature of the etiology (internal or external) or the patient’s symptoms. If possession is diagnosed, one first proceeds to the internal dragons treatment.

Worsley’s blocks to treatment are all employed in a specific sequence. In an initial treatment, if a patient is diagnosed with possession, it should be treated before draining Aggressive Energy[41] or clearing a Husband-Wife block (if present). After clearing possession, Worsley advises the practitioner to treat the patient on their “level” and use command points[42] to anchor the treatment and prevent recurrence.[43] Source points on the patient’s C.F. are recommended to conclude a possession treatment. Worsley (2012) writes:

Just as sickness does not occur on one level alone, so there are no acupuncture points that affect one level alone. The least to the most experienced practitioners will most frequently use the command points which beneficially affect body, mind and spirit in a variety of ways. Simply using a source point also helps to restore balance at all levels simultaneously. It is thus possible to treat the spirit with command, source, and simple element points. There are, however, certain points that reach the spirit even more directly. If a person’s illness is primarily at this level, we may select these points in order to bring help directly to his spirit. [44] (pp. 184-185)

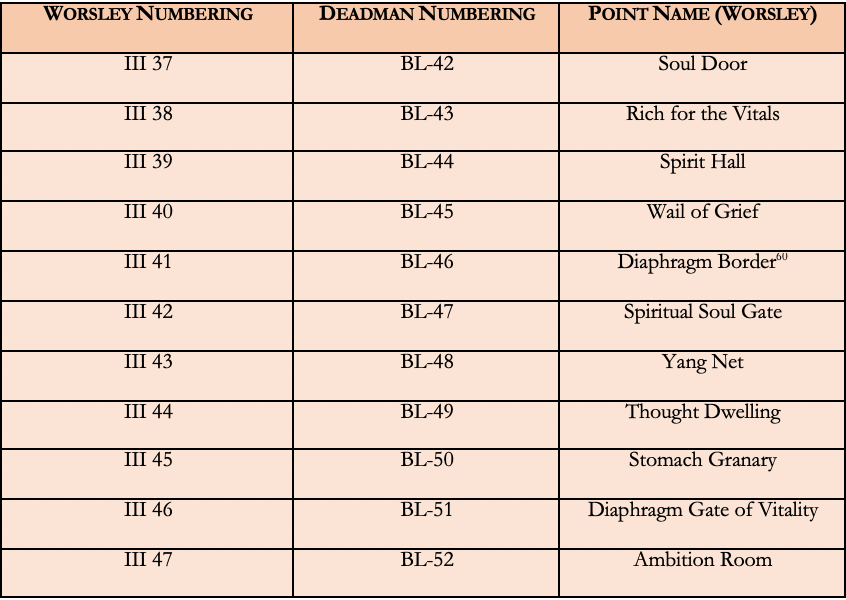

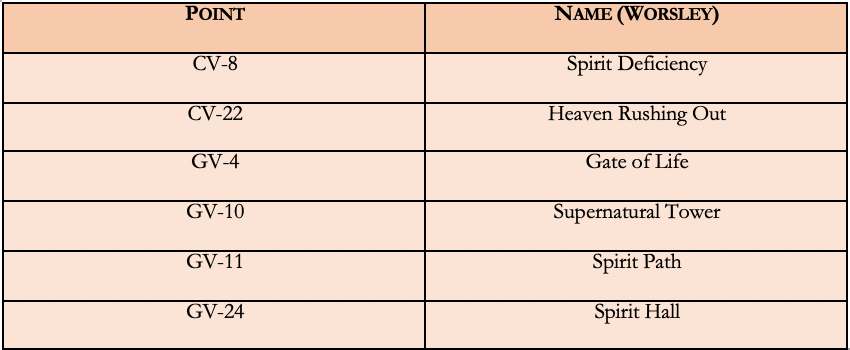

Worsley is referring to points on the upper Kidney meridian and outer Bladder meridian. These points (along with points on the Conception and Governor Vessels) are used in the context of treating any C.F.[45] A majority of these points have “spirit” or “soul” in their names. [46] (See Appendix D). Worsley’s emphasis on possession, point names, and the spirit of the patient makes his approach a revival of Tang dynasty values, especially as seen in Sun Simiao.

According to Judy Worsley, "A person becomes possessed at a point when they are vulnerable. If they do not move beyond that vulnerability through treatment and lifestyle, then possession could recur”. (Judy Worsley, personal communication, 2022). To prevent recurrence, we have to consider the treatment as a whole. After clearing possession, Worsley recommends draining Aggressive Energy as a standard procedure, even if Aggressive Energy has been drained in previous treatments. Any of the points referred to above can be considered following a possession treatment to further support the patient’s spirit level and to prevent recurrence. However, the “less is more” maxim applies here, and our point selection is carefully considered to support the patient post-possession without overtreating.

Treatment as Exorcism

Although Worsley interprets possession as a psychological imbalance, a shamanic perspective still pervades his perception, especially in his discussion of patient reactions to the possession treatment:

This reaction can be so mild as to be scarcely perceptible, but in some cases, it can be dramatic, and we should be prepared for it. In the clearing process, many patients will experience a degree of shivering or uncontrollable movement. (Worsley, 2012, p. 173)

Worsley’s description reads identical to what one envisions in an exorcism. We can also understand shaking movements as a natural response to the re-introduction of the life-force where it was previously stagnant, deficient, or blocked. Such movements are similar to the purifying movements (kriyas) that yogis experience when the Kundalini awakens and courses through the body. The “serpent power” of the Kundalini shares symbolism with the East Asian dragon—both are alchemical archetypes of inner transformation and spiritual awakening.[47]

In “Depression and demonic possession: the analyst as an exorcist”, Asch (1985) compares the process of psychoanalysis to exorcism:

Psychoanalysis has evolved a concept of depression that deals with ideas about introjects,[48] rather than conceiving of them as concrete toxins or demons. Psychoanalytic treatment is a cognitive technique for "exorcising" certain identifications by delineating them and then neutralizing them through understanding.

Where psychoanalysts view demons as introjects, acupuncturists view demons as energetic vacancies. Where psychoanalysts exorcise through understanding, acupuncturists incise with needles.

From Possession to Obsession: Blocked Affect as Block to Treatment

In The Discovery of the Unconscious, Ellenberger (1970) asserts the origins of psychotherapy in exorcism:

Exorcism has been one of the foremost healing procedures in the Mediterranean area and is still in use in several countries; it is of particular interest to us because it is one of the roots from which, historically speaking, modern dynamic psychotherapy has evolved.

Ellenberger’s supposition is confirmed by Jung in a memoriam written two weeks after Freud’s passing on September 23, 1939:

Freud owed his initial impetus to Charcot, his great teacher at the Salpetriere. The first fundamental lesson he learnt there was the teaching about hypnotism and suggestion, and in 1888 he translated Bernheim`s book on the latter subject. The other was Charcot’s discovery that hysterical symptoms were the consequence of certain ideas that had taken possession of the patient’s “brain.” Charcot’s pupil, Pierre Janet, elaborated this theory in his comprehensive work “Nevroses et idees fixes” and provided it with the necessary foundations. Freud’s older colleague in Vienna, Joseph Breuer, furnished an illustrative case in support of this exceedingly important discovery (which, incidentally, had been made long before by many a family doctor), building upon it a theory of which Freud said that it “coincides with the medieval view once we substitute a psychological formula for the `demon` of priestly fantasy.” The medieval theory of possession (toned down by Janet to “obsession”) was thus taken over by Breuer and Freud in a more positive form, the evil spirit—to reverse the Faustian miracle-being transmogrified into a harmless “psychological formula.” It is greatly to the credit of both investigators that they did not, like the rationalistic Janet, gloss over the significant analogy with possession, but rather, following the medieval theory, hunted up the factor causing the possession in order, as it were, to exorcize the evil spirit. Breuer was the first to discover that the pathogenic “ideas” were memories of certain events which he called “traumatic.” This discovery carried forward the preliminary work done at the Salpetriere, and it laid the foundation of all Freud`s theories. As early as 1893 both men recognized the far-reaching practical importance of their findings. They realized that the symptom-producing “ideas” were rooted in an affect. This affect had the peculiarity of never really coming to the surface, so that it was never really conscious. The task of the therapist was therefore to “abreact” the “blocked” affect. (Jung, 1939).

It appears that both Freud and Worsley propose an interpretation of “possession” as a “block”—for Freud, it is a “blocked affect”, for Worsley a “block to treatment”.

Instrumentality: Practitioner as Medium

Here, it is worth recalling Kaptchuk’s remark about Worsley as a shamanic healer. Eckman (2007) recounts:

Ted Kaptchuk mentioned to me, after watching Worsley at work, that he thought Worsley was the greatest shamanistic healer he had ever seen. I think this is an aspect of our profession that needs to be brought out into the open, and Worsley has constantly stressed that developing the deepest possible rapport with patients and then allowing yourself to become an instrument for forces beyond your own personal power, is what we should all be striving for. That’s a good definition, as far as I’m concerned, of a shaman.

Worsley emphasized the function of the practitioner as an “instrument of nature”, an emphasis that invokes the shaman as a medium. However, in Worsley’s tradition of acupuncture, the practitioner is not an instrument for spirits, guardians, or entities of any kind. Rather, nature is the force that moves through the practitioner. Thus, nature itself is the agency of treatment, and the practitioner is nature’s instrumentality. Eckman (2007) later confirms our earlier premise when he writes, “Acupuncture itself likely originated from the exorcistic practices of the early shamans or wu”. (p. 215)

Internal Dragons

Returning to the seven dragons, the origins of Worsley’s treatment protocol remain somewhat mysterious. Worsley states that he learned the protocol from his Master Hsuie. (Eckman, 2007).[49] Eckman’s research suggests the origins of the internal dragons treatment as a Tang dynasty protocol:

The Internal Dragons treatment, including the Master Point on the conception Vessel, was identified as a Tang dynasty prescription for hysteria by an aged acupuncturist interviewed by Allegra Wint at the Yunnan College of TCM in Kunming in 1982. (Eckman, 2007, pp. 227-228).